Co-starring

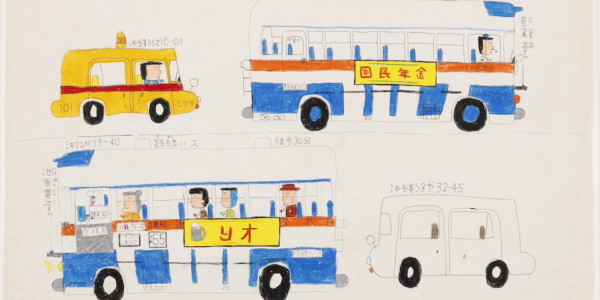

HATANAKA Tsugumi(1973-)

Hatanaka was born in 1973. She lives in Hokkaido. She lives with her parents and at a group home, creating art at home on her days off. The motifs she depicts include small birds, flowers, trains, and sumo wrestlers. For a period of time, she was interested in lights, and drew mercury lamps, paper lanterns, and stars among other things. Her works have been shown in the Hokkaido Outsider Art Exhibition at the Asahikawa Museum of Art in 2009, the Art Brut Japonaise exhibition at the Halle Saint Pierre art museum in Paris in 2010, and at the TURN – From Land to Sea exhibition at the Mizunoki Museum of Art in 2014.

![[Photograph (Works)]](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/62bfd346a6fea066899922c4069523fa.jpg)

“Gate Lamps (2 Lights)” / 210×297mm / Crayon on paper / 2003 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

When I saw this work, the first thing which crossed my mind was when I went to Thailand for filming. In a very rural area, we went up a mountain, and there was a single utility pole there.

Power lines ran up from the bottom of the mountain to that utility pole, but there were no utility poles or power lines beyond it. In other words, power wasn’t being delivered beyond that point yet. So I had seen a utility pole like that before.

![[Photograph (Works)]](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/e35900058cce217f7be2d59e5305c36c.jpg)

“One Naked Lightbulb” / 380×275mm / Crayon on paper / 2003 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

I imagined a story. A story about a village with a house with power and a house which wasn’t getting power yet.

The house with power had lights, and even at night, was not dark and enjoyed the convenience of being able to do everyday things. A girl lived in this house, but her very good friend’s house did not have power yet. So when it became night, her friend immediately had to go to bed.

The girl who lived in the house with power, however, stayed up late into the night, doing all sorts of fun things under the lights. When the girl in the home without power heard about this from the girl in the home with power in the daytime, she thought how nice it must be to have electricity.

Of course there were people here and there in the village who wanted to use electricity. But they were resigned to the belief that they could only wait until they got it. After all, they didn’t know when they would get it.

It was around this time that a rumor began spreading that an electronics store would open up at the foot of the mountain. This rumor reached all the way to the top of the mountain without power. At the same time, another rumor reached them that someone had started a business selling extension cords. That a man who wanted to open an electronics store but couldn’t get it to work was making a lot of money with extension cords.

Anyway, the extension cord man eventually made his way to the village at the top of the mountain. He plugged an extension cord into the utility pole near the house with electricity and brought power to the house of the girl’s friend who had so wanted electricity. They did this by connecting several extension cords, each dozens of meters long.

![[Photograph (Works)]](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/6838beff7b0b1e7a6ac4a6a767244279.jpg)

“Two Naked Lightbulbs” / 380×272mm / Crayon on paper / 2003 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

Now that she had electricity, she could play at night, as well, and the girl whose house hadn’t had power was very happy. The “amazing extension cord man” became the talk of the village, and he became very popular.

His extension cords, however, were surprisingly expensive.

They were expensive, but everyone was willing to pay for them in order to get electricity.

As a matter of fact, this village had a mine, but because it got dark, they had to stop working in it at night. Thanks to the man’s extension cords, however, they were able to use electric lanterns to light up the minehead and shaft, allowing them to work even at night. The men of the village worked and worked.

![[Photograph (Works)]](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/e3603eb9bd64988da250b744fa4d33d5.jpg)

“Lanterns (2 Lights)” / 211×152mm / Crayon on paper / 2004

“Lantern (1 Light)” / 210×149mm / Crayon on paper / 2004 / Both in the collection of The Nippon Foundation

I imagine after they worked they wanted to go to a bar, and so now a bar lit by a red paper lantern opened in the village.

![[Photograph (Works)]](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/5e89653aaa730c09a4daf65f4ece88ae.jpg)

“Red Paper Lantern (1)” / 210×150mm / Crayon on paper / 2004 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

At first there was just the one bar, but then it increased to two and then three, and the village became more and more bustling. All thanks to the extension cords.

![[Photograph (Works)]](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/280716b268184b47c08fd18f2c0d4ecd.jpg)

“Red Paper Lanterns (2)” / 210×150mm / Crayon on paper / 2004 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

Time passed and at last the day came when power was to be delivered to the village at the top of the mountain. Utility poles were erected, power lines were ran, and each home was lit by electricity. Accordingly, extension cords were no longer necessary.

Thereupon the extension cord man came again. His thing was to buy back the extension cords he had sold to the villagers and bring them to another village where there was not yet any power to sell again.

The extension cord man was a greedy fellow who made lots of money this way, repeatedly buying and selling extension cords. As he was travelling around the villages without power making money, however, his conscience began to bother him. His heart would twinge watching the children be so innocently delighted by electric lights.

“I can’t make money like this,” he thought.

It was the evil nature of taking advantage of people in a weak position inherent to this business which made him feel this way. He had started this business without thinking, but now he had been bothered by it for a long time. Now that I think about it, I think the villagers might have been saying how he had an ill-omened face like that of a binbogami, a wicked spirit which brings poverty.

The extension cord man revised his prices, and decided to buy back the extension cords he had sold for the equivalent of 100 yen for 80 yen. The wholesale price of the cords was 20 yen, so he didn’t make any money doing this.

Furthermore, he felt he had to do something more for the first village he had sold the extension cords to. He decided to gift the village with its very first streetlight.

![[Photograph (Works)]](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/9b6b9a39092a633a37eaaeb0fdf7a3f1.jpg)

“Single Light-style Blue Nightlight” / 256×177mm / Pastels on colored paper / 2003 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

With the gift of the streetlight from the extension cord man, the village created a public square.

Thanks to that streetlight, the square was brightly lit even at night. The villagers would talk about all sorts of things there, deepening their friendship and love for each other, and in both name and substance, the village was made more prosperous and abundant.

…Although the extension cord man did not know that his gift had brought such benefits. The reason why is because he had quickly gifted the streetlight and then moved on to another mountain.

With the extension of electricity, the extension cord man would find yet another area further along without electricity, bringing extension cords with him. One day, however, he finally went out of business. As far as the extension cord man could tell, every single village had gotten electricity.

Everyone was happy that their lives were bright with electric lights. The former extension cord man now toiled away in a field, living a life of self-sufficiency. Eventually, the man married the daughter of the farmer next door, had a child and, with the passage of time, a grandchild.

Around the time that grandchild became a teenager, an unprecedented boom in extension cords was happening in the world! Now, in addition to a variety of electric appliances, it was the age of the internet. People needed cords and cords to connect their computers. Along with this, cords were also needed for conventional electric appliances. Every home was a tangle of cords. Extension cords had the power to instantly untangle this mess.

The grandchild said to the now very old man,

“Grandpa, I’m going out into the world to make my fortune with extension cords!”

The old man replied,

“My grandchild, sell your cords for 110 yen!”

![[Photograph]ちゃぶ台の原稿用紙に、肩肘をつきながら向かうイッセー尾形さん。](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/235fc5c8aaf187aff27bcf54db23f72f.jpg)

![[Photograph]書きながらも、右上を見るイッセー尾形さん。](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/1c0be28021264b0c8d76a8a9a3badc10.jpg)

![[Photograph]書きながら、右横をにらんでいるイッセー尾形さん。](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/a20ea0b266bb9e3630c843752046d3da.jpg)

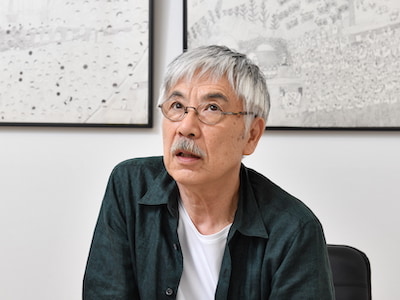

Issey Ogata’s Wildly Imaginative Art Appreciation Techniques

As actor, playwright, and director of his one-man show, Issey Ogata brings new worlds to life every day. We asked him for tips on having fun with the power of unfettered imagination.

Stories come alive when responsibility emerges from irresponsibility

Seeing these pieces reminded me of how interesting lightbulbs are. When you think about it, lightbulbs are one of the first examples of civilization you encounter when you are born and grow up in this world.

When you are a baby wriggling under an electric light, you are constantly looking up at it. I imagine that’s why we have this attraction to lightbulbs, because we feel this kind of familiarity with them.

When I engage in my wild imaginings, I start with this kind of irresponsible thinking and then take responsibility to build on it. Like thinking about how to create a story from a naked lightbulb.

I don’t directly know the people who make the works, nor do I know the background or basis behind their creation. In that sense, they are people who are not close to me. That enables me to be irresponsible, to imagine whatever and do whatever.

However, because I know this is irresponsible, I take responsibility to expand and develop my premise. There is enjoyment to be had in the journey from irresponsible to responsible. It is the joy of creation.

Creating something brings about responsibility. Responsibility always follows in the creation of something. The desire to proceed further, to go beyond comes from no one else but yourself, and thus in the end you move forward by your own words. When I’m in the middle of creating something, I may not consciously be aware of the responsibility I am taking, but others watching will think, “he’s taking the responsibility to do that.”

When I encounter a piece and think “well that’s interesting,” its the start of an irresponsible process of enjoyment. And when I decide to build on that in my own way, I’m beginning to take responsibility. That’s how it looks to people watching from the outside. That series of events.

So I hope that when people see the things that I have made, it gives them irresponsible inspiration, and that they take responsibility to build on that. And connecting that together, we can create a great circle of irresponsibility and responsibility.

The result could be a picture or music or anything, but I think it would be interesting to see that become a great circle.

Put yourself in an ambiguous place and enjoy the controversy and conflict this creates

My story in this article came alive thanks to the combination of the isolated utility pole I saw deep in the mountains of Thailand long ago.

I love frontiers. Places that are the boundary between an area steeped in civilization over here and one not over there. In find them fascinating. There is room for debate about where civilization ends and the uncivilized begins. Someone involved will say “It’s here,” and another person will say “No, it’s definitely over here.” Needless to say, this kind of conflict and dialogue doesn’t just occur between two people talking, but also inside oneself.

When I create something, it’s often a dialogue of some kind when you get right down to it. There are limits to this with a monologue, but when two people talk, you can expand and go in different directions.

To somewhere civilized or uncivilized. Personally, I like to take things to that boundary, to the frontier. Once you’re in civilization, there’s no need to worry. There are places, however, which you can neither call civilized or uncivilized. They have aspects of both, and that’s the most interesting to me. You could call them either, and they can be either. And that makes you want to hear what other people think.

The extension cords in our story this time serve as a bridge connecting the two. A tool that, when it comes down to it, are part of civilization, can solve a problem in the frontier. We’ll figure it out one way or another with what regular people can do. I love that kind of thing.

Alongside unresolved thought, there is also wild imagination

When you go about creating something like this, you mostly don’t notice it going on. However, I am much more interested in how something gets created rather that what gets created.

We call this the creative process, but it’s impossible to determine just when the creation is created. The reason why is because the clearly defined and the not clearly defined both exist within us. The number of things which we can give clear shape to and convey to other people is extremely small. Things spend much more time as unresolved thought. Much more of our life is spent on those moments.

I recently realized this, but there is no blanks in their awareness. We always conscious while we are alive. Even granting that we are not while we are asleep, we are always conscious while awake. I’m not talking about focus. Even when we are bored, we are still conscious. This being so, I think human beings, each and every one, are doing something amazing. Because they never take a break.

I came to this conclusion because I’m an actor, and an actor must constantly think about consciousness while on stage. I can count out the things I’m conscious of on stage. For example, “If I say this line now, what will the audience think?” “I’ll say this next; okay, here we go.” “Saying that got this reaction.”

But when I think about how human beings are always conscious, that they have no blanks in their awareness, I think that small number of things can’t possibly be all I’m thinking about. I’m sure I’m conscious of more, but the number of things I’m aware I’m conscious of is small and I can’t seem to increase that number. On stage.

In philosophy, they talk about being conscious of what you are conscious of, and everybody does that, but in the profession of acting, I think it would be good to consciously increase that and do it more precisely.

…These are the kinds of things I think about regularly, and they too serve as fodder for creation, and from that irresponsibility responsibility can arise.

Attracted by lightbulbs and interested in them, I wondered why I was so attracted. And I realized that it was rooted in the experience of looking up at them as a child. Because these kinds of experiences mix together, what starts out as irresponsibility gradually gains focus and becomes the desire to share a story. I think that process in turn gives rise to responsibility.

![[Photograph]ほおづえをついて居眠りをするイッセーさん。](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/7a88dbebbf4f7e74ab0b1dcbc25b0f91.jpg)

![[Photograph]ほおづえをついて居眠りから覚めるイッセーさん。](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/d114e0c3a3fb1e46d9acca4d939a07c3.jpg)

Note: This is the final story in “Issey Ogata’s Wildly Imaginative Art Appreciation Techniques.” Thank you for joining us in this delightful world of wild imagination.

[Corporation] Yanaka no Okatte, NPO Taito Cultural & Historical Society, Ueno-Sakuragi Denchu Hirakushi House and Atelier

![[Photograph]和室。丸いちゃぶ台を前に座り、万年筆をもち原稿用紙に向かうイッセー尾形さん。なにか考えているのか、顔は正面に向き、眼光鋭い。](https://www.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/7e47e7e300bdea0bb10a1c8391801c32.jpg)