Co-starring

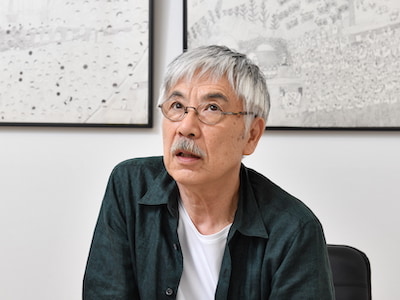

ITO Mineo(1964-)

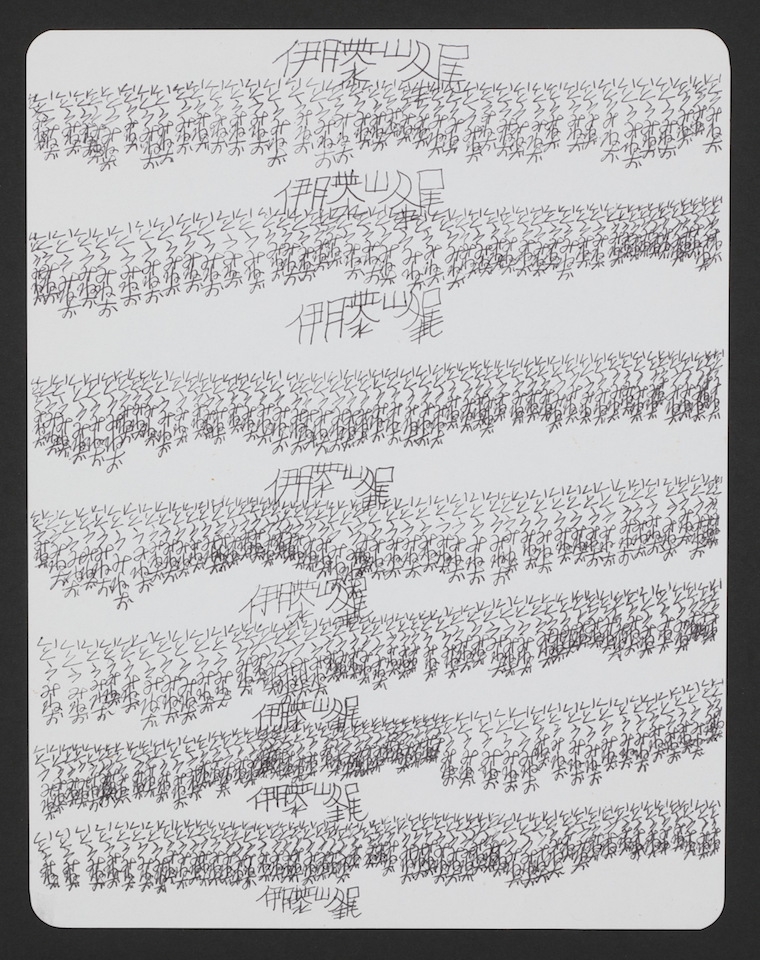

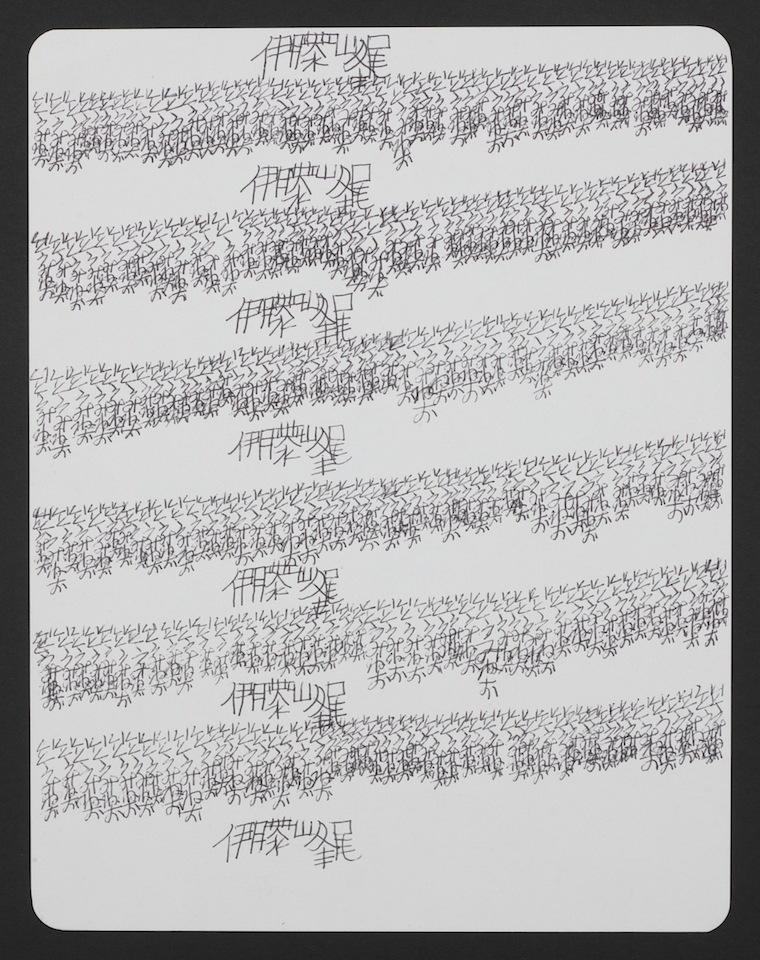

“ITO MINEO” 245×190mm / Ballpoint pen on white cardboard / 2003-2008 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

My first thought when I saw this piece was that it must be sheet music. When I looked more closely, I realized that it’s actually someone’s name, but let’s not get too hung up on that. Let’s embrace my first-glance impressions.

For sheet music, it’s a little unusual—rather than the ups and down you might expect, it’s a monotonous and fairly repetitive melody, isn’t it? Just look at the low notes all clustered together, while the high notes pound out at the same interval.

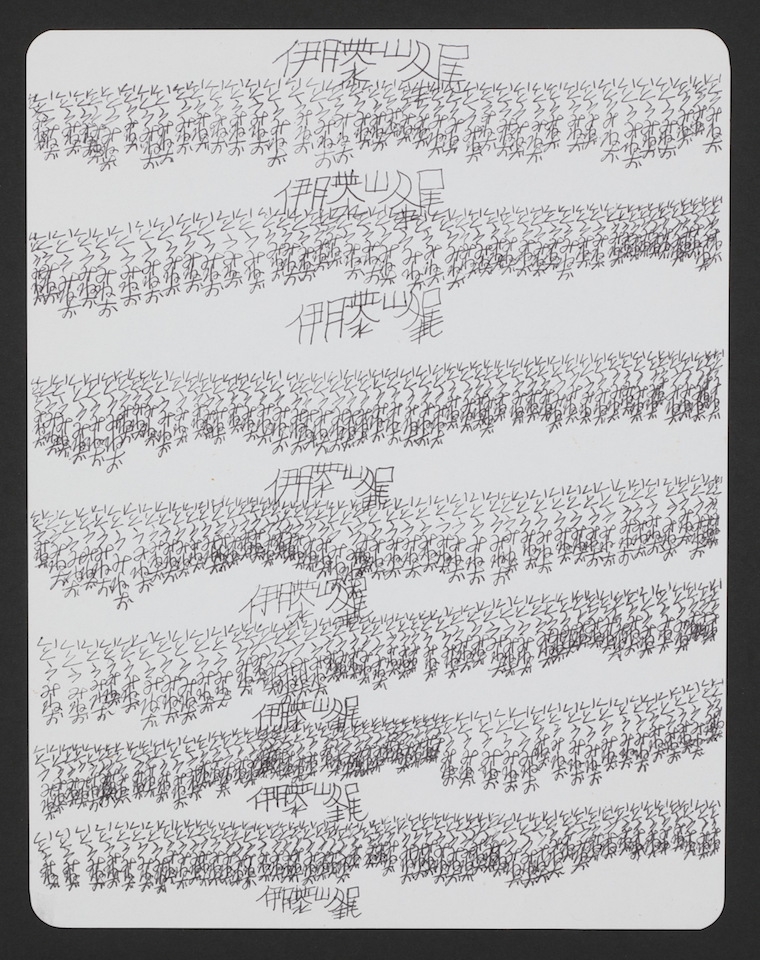

Because he can barely see any more, every composition he plays—whether it’s Brahms or Tchaikovsky—he plays from memory. This is how he can still play, despite being unable to see. As a result, he rarely even picks up a piece of sheet music these days, but with something that looks like a score right in front of him, he takes it up for a look. Yet it blurs before his eyes and he can’t see it clearly.

“ITO MINEO” 245×190mm / Ballpoint pen on white cardboard / 2003-2008 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

Nevertheless, something about it calls out to him, so he takes it home, sets it up in front of the piano, and, managing to read it somehow or other, plays. Then, wanting to memorize it, he practices it over and over. Yet no matter how many times he plays it, he feels that something is missing.

He is an incredibly famous pianist in Russia. He lives in a quiet, upscale residential area, in a house on “Elm Tree Road,” named for the elms lining the street. The residential area continues across the street, and a diplomat and his family have moved in there. This family across the street has a daughter. As a diplomat’s daughter, she barely settles at one school before it’s time to transfer again, and she has no time to make friends. She’s lonely, but she’s learning to play the flute, and this flute is her friend. She has no idea whether she’s any good or not, but when she blows into her flute and listens to the sounds it makes, she feels calm.

One day, she hears the sound of a piano from the house across the street. The musician is, of course, our elderly pianist. She listens carefully, but she’s left feeling somehow unsatisfied. There’s nothing wrong with it, but she finds herself wondering, ”isn’t it missing a central melody?” That’s how she ends up taking matters into her own hands and playing along on her flute, trying out different melodies. Quietly, listening carefully. Day after day, she keeps it up. And as she does, the melody gradually takes shape, while the elderly pianist continues to play and play until he succeeds in memorizing the score.

The girl was having fun every day. ”Wouldn’t it be great if we could keep this up until we perfected it?” she thought. Yet in no time at all, her diplomat father is sent to a new country and she has to move. The elderly pianist knows nothing about any of this, however, and simply continues to play his own part alone after she’s gone. “You can’t hear that beautiful music any more, can you?” the people who live on Elm Tree Road say regretfully to one another.

Did he ever make up for that “something missing” that he had sensed? I’m afraid it’s unlikely. Perhaps the knowledge that it would work if he added a certain melody was somewhere within him, too, but after all, you know, he’s a serious musician who graduated from a national music school, so he can only play what the sheet music tells him to.

“ITO MINEO” 264×199mm / Ballpoint pen on white cardboard / 2003-2008 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

The sound of these two strands coming together could only be heard by the people who lived on Elm Tree Road. And so goes the tale of Russia’s phantom musical masterpiece.

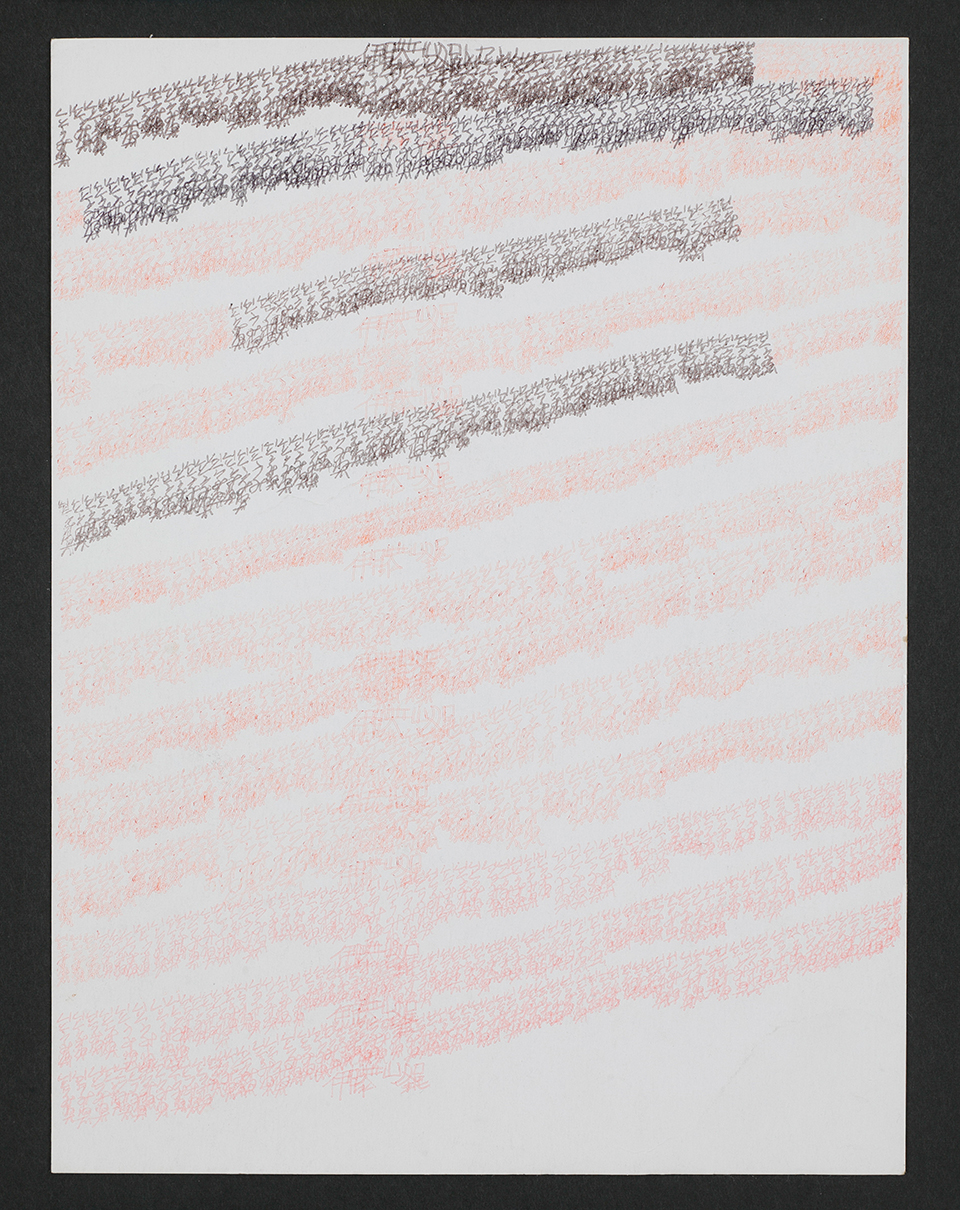

“ITO MINEO” 245×190mm / Ballpoint pen on white cardboard / 2003-2008 / Collection of The Nippon Foundation

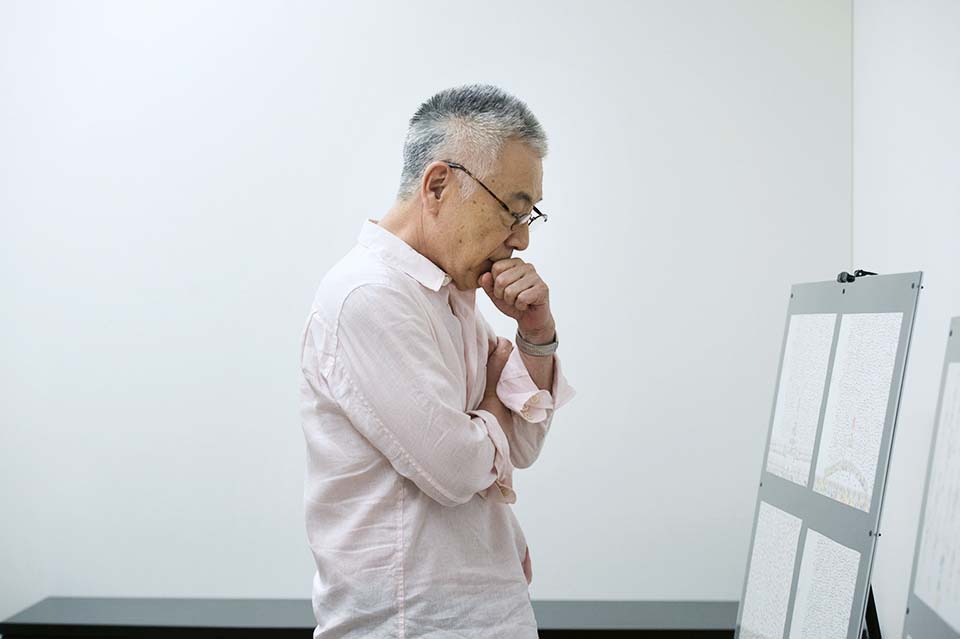

Issey Ogata’s Wildly Imaginative Art Appreciation Techniques Part 1

As actor, playwright, and director of his one-man show, Mr. Issey brings new worlds to life every day. We asked him for tips on having fun with the power of unfettered imagination.

How do we bridge the “gap” to approach the treasure?

When we’re coming up with ideas, whether for a story or for a novel, I suspect that many of us think as though we’re talking to someone. When a child—or anyone else—is making up a story, they tell their story in such a way as to grab their audience’s interest, checking back to see if they’re paying attention. Of course, if we want people to listen, we have to be excited about our stories ourselves, but I think we have this kind of hypothetical audience in mind when we’re doing our thinking.

The secret to my creative flights of imagination is to keep the “treasure” at arm’s length. For instance, let’s take a piece of sheet music—isn’t it more interesting if you can’t see it clearly? I’m more fascinated by the things I can’t reach than the things I can see properly. It’s all over when you take the treasure in your hands, so maybe it’s about being unable to easily grasp it and enjoying that distance.

When an object goes somewhere, there’s necessarily a gap. But this is not a punishing gap, it’s a fun gap. The very act of bridging that gap gives rise to emotion: sadness, amusement, hilarity, tragedy. Perhaps the further you get across the gap like this, the more the treasure sparkles. If it’s perfect from the very beginning, isn’t it all over? Maybe there’s also part of me that just doesn’t want to let it end.