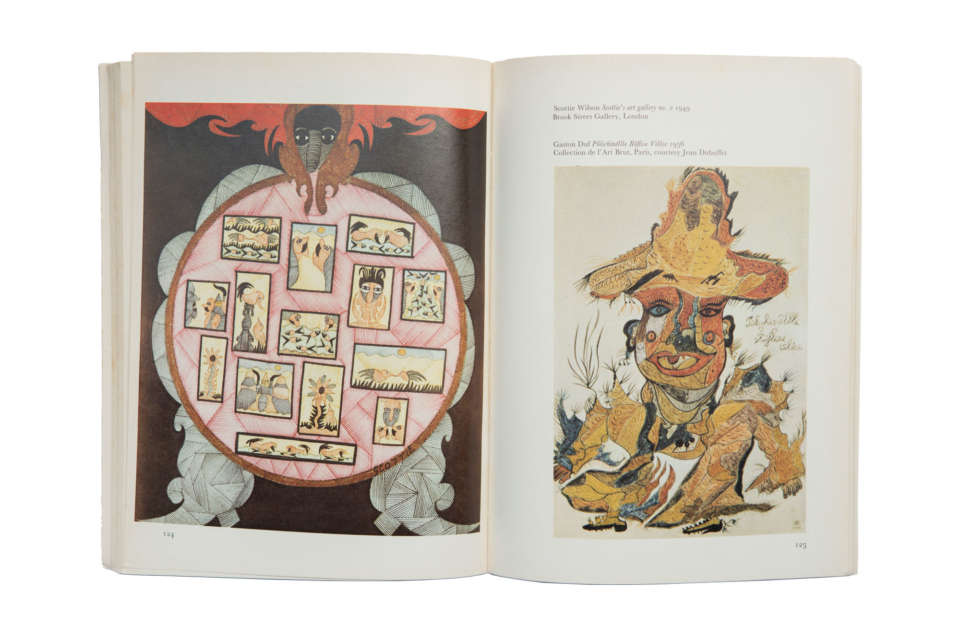

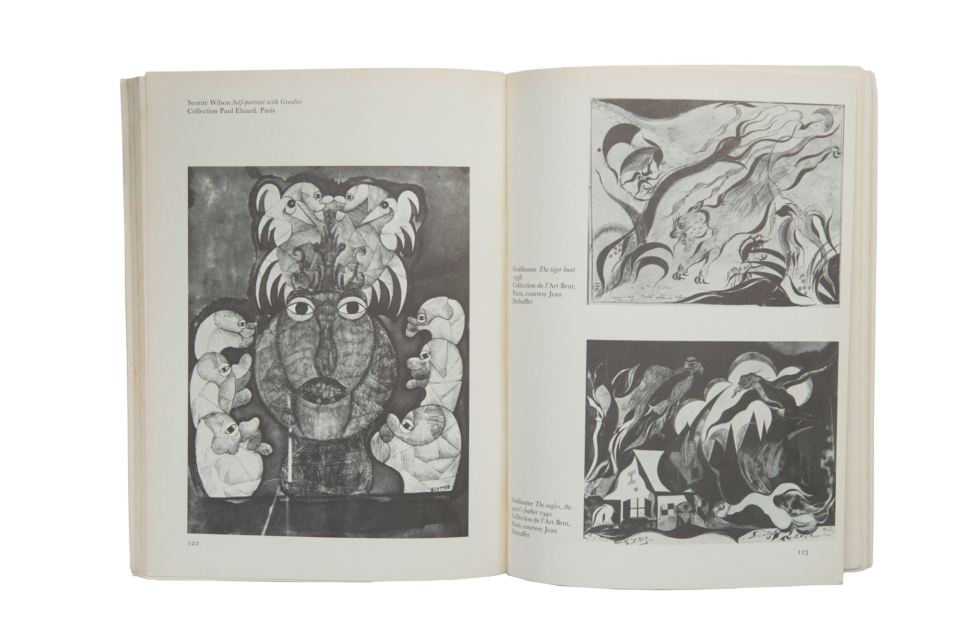

Scottie Wilson’s artwork from “Outsider Art”, mentioned in the interview.

Why do they draw? A study of the inside of the outsider artist.

Roger McDonald: For these artists, the trigger for creation can be something quite trivial.

Roger Cardinal: For example, Scottie Wilson01 started his career from doodling improvised drawings on the surface of a table with a fountain pen that he found in a secondhand store in Toronto. How these individuals, who we call outsider artists, find their artistic methods are often quite mundane. However, the artworks are extraordinary. For artists with mental disorder, who are central to art brut in Europe, their creativity is often triggered by wounds, disappointments, and trauma from the past. There are many reasons for something unfortunate to happen to people, but not everyone is compelled to draw or to make something visual from these misfortunes. Those who are, are driven by the need to express and what we ask next is: “who are they expressing towards?” Some people may be very satisfied with their life, always treated well and never feeling disappointed. However, at 80 years old ready to conclude life, something can trigger this person to be brave enough to start drawing.

Why do people draw? That’s because to draw “something” makes “you” feel happy. In these moments “you” probably don’t want to be rushed. For example, if someone is sketching while thinking that they have to finish by 5 pm, that’s probably not going to turn out to be their best work. When you force people to draw, like in school. you cannot access the highest expression that comes from within.

McDonald: Which art should be, fundamentally.

Scottie Wilson’s artwork from “Outsider Art”, mentioned in the interview.

Cardinal: Yes, and it doesn’t have to be a drawing either. It can be a sculpture, a doodle, graffiti, or even a chalk scribbling left on the pavement in front of the National Gallery. Drawing is a way to tell the outside world what “you” feel is urgent. It is way for other people to understand. Most importantly, it is to understand artistically “yourself.” Artists in general know that the artwork comes from within. They also remember what didn’t work, where it didn’t fit on the paper and what had to be added later. They intimately know their artwork and can recognize it even years later.

They also don’t necessarily want to sell work which they are attached to. From our conversations, many of the outsider artists that we based our study upon were not educated in art or had a desire to work as an artist, and therefore did not have funding either. They also didn’t have family members that could give advice or people in the real world to say; “your work is fantastic, I want to show this to my friend who owns a gallery.” On the other hand, to support them as artists also has its risks.

McDonald: So, there are possible situations where the artist does not want their work to be recognized and sold at galleries?

Cardinal: Yes. Wilson, who is from Scotland, was illiterate but taught himself how to express through drawing and continued while working as a street vender. He was not very interested in money and sold his drawings for nearly nothing to people who liked them. He had only participated in one or two exhibitions in Toronto, but when he returned to the U.K. in 1952, people started to recognize his talent. One time, his work was exhibited in extravagant frames at a London gallery. Sherry wine was served at the opening, but when Wilson saw the gallery from outside he thought: “This is not me.” He had with him several drawing that he planned to show gallerists that were priced for 150 pounds each in the gallery and started to sell these that at a very low price to people passing by on the street.

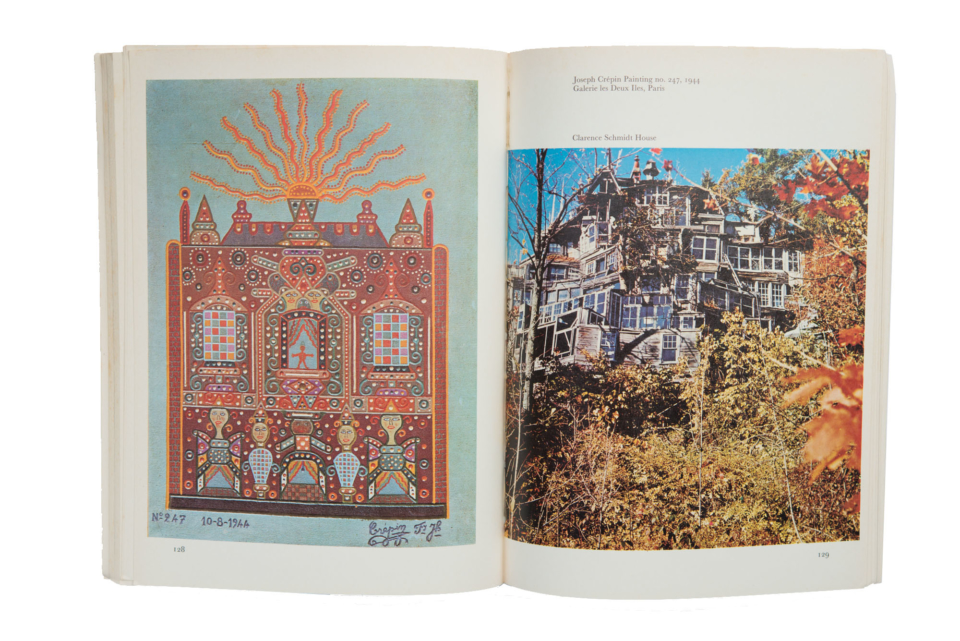

From “Outsider Art”. Left page is the work of Joseph Crepin (1874-1948), a French tin roof craftsman and public medical worker who started drawing spiritual paintings at the age of 65. Right page is Clarence Schmidt’s (1897-1978) 《Mirror House》. Schmidt worked as a plasterer and his 《Mirror House》 was seven stories high built with scrap material and covered with mirrors, located on the hillside in Woodstock.

The unconscious - What many artists desired to access but couldn’t.

McDonald: In your book you have a beautiful expression, “possessed of an expressive impulse.” Are you implying connections to traditions in shamanism or other sacred mediums, and trance states?

Cardinal: I like stimulating ideas. These “descend” from somewhere and trigger an impulse that tells us something has to be done. If we borrow the words from medieval Christianity: “To resign yourself is to give your soul great power.” The things that you mentioned are of great interest to the anthropologist, but I would like to emphasize that these are also included in the research of outsider art. For example, many cave art have the same pure qualities as outsider art. As far as I know, there were no rules or masters, and nothing was enforced. This art can be seen as a highly unique system of symbols that was strong enough to release unconditional joy and to produce a desire to live, preventing death.

McDonald: What I find interesting is that many mainstream artists use various methods to artificially trigger an altered state of consciousness. Perhaps Henri Michaux02 who used mind altering hallucinogens not for pleasure but as a conscious experiment for poetry and expression is a perfect example.

There has been a fluid exchange between so-called “insider art” and outsider art. I wonder how much Dubuffet was aware of these when he wrote his text, because it seems like he is rigid and rejects things that do not fit his own definition of art brut.

Cardinal: To answer that, we have to go back to the era of Romanticism03 and Modernism04. As an artist, Dubuffet was involved with many other artists, but he was particularly interested in Matière05. He also was able to objectively judge his own work, which were all numbered and labeled, and say: “Let’s stop here and move on.” Perhaps this self-discipline that he naturally had also played a role.

McDonald: In his own activities as an artist, Dubuffet was conflicted in trying to explore new expressions that would liberate him from the closed-minded art world. And he was also very stringent. Perhaps spiritually he wanted to be an outsider artist.

Outsider Art – More inclusive than art brut

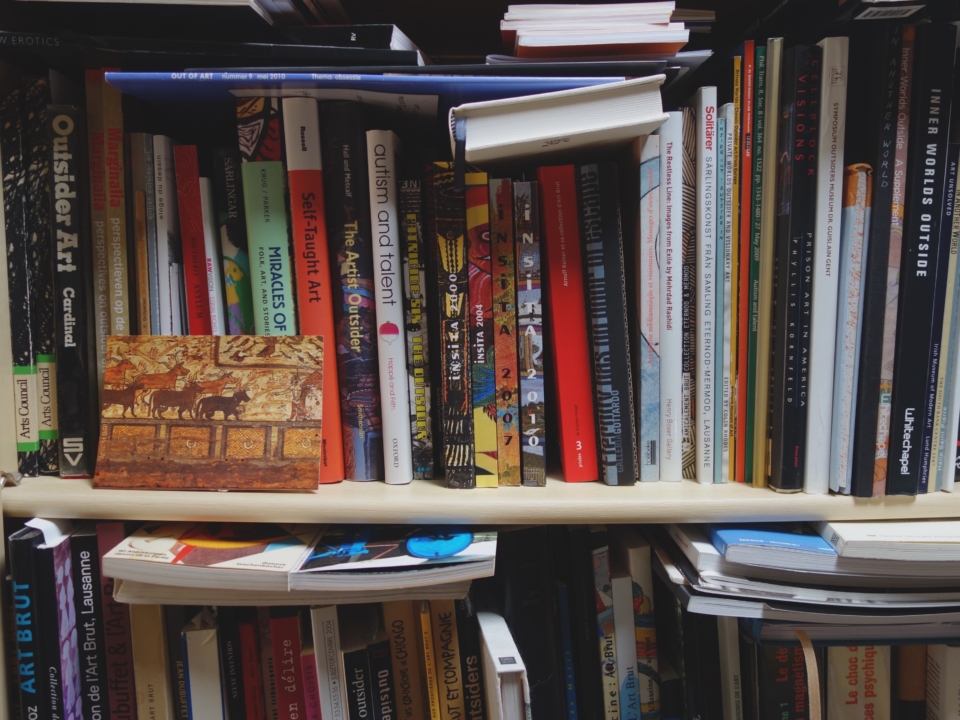

McDonald: It seems that your book “Outsider Art” is more inclusive, taking a more flexible and tolerant approach than Dubuffet’s.

Cardinal: At first, I wanted people to know about Dubuffet. As I summarized his writing, I included the context of art that he attacks, with its foundation in the art academy that suppresses intuition. I sympathized with his critique. I liked how Dubuffet says: “The critic stands on unstable grounds.” As you implied, I also introduced an inclusiveness that he did not have. However, if I look back with skepticism about my taste and objectively question why I included such artists in the book, I recognize my own weaknesses. There are some parts in the book that I wouldn’t have included today. The material that I saw during my research was also limited. For example, I didn’t make it to Russia to respond to a certain message that was sent to me. I do think that in the larger sense, I was able to give depth to what Dubuffet put forth in art brut. I translated his thoughts into English, and found an appropriate title for the book, so you can say I was his interpreter. What is an artist that is not an artist? This is a paradox. What is an artist who is fantastic because they were never assisted, educated, or does not know how to describe the colors used in their artwork? How can people be so absorbed in drawing something? I dedicated all my energy into this book with a foolish ambition to turn the London art scene upside down. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen.

McDonald: Do you think it really didn’t happen? What is curious when you look back at history, is that while keeping the word art brut intact, outsider art has grown and expanded far beyond it.

Cardinal: Today in France, many artists are aware they are categorized as art brut and have no problem with it. French culture as a whole has praised art brut and people know the artists. This tendency is more prominent than in the U.K. I was careful not to mix myself up with Dubuffet. I needed to introduce pioneers such as Leo Navratil and Hans Prinzhorn, that came up earlier in our conversation, to present a different approach to the material and highlight issues that emerge through carefully examining the work. Psychiatrists and psychotherapists talk about art in a completely different way than the public does.

McDonald: Would you say that for outsider art what is most important is the way we view it?

Cardinal: Yes. For example, if you could look at one painting for more than five minutes, you can lead yourself into a completely different state. Originally art can bring depth and expand the inside of the viewer. As we take time to look at art we start to immediately notice the issues that it embodies. Once we do this, most of us will stop caring about the artwork’s prices or its external value, and will start going to The National Gallery06 to see art.

*Interviewed on 2017

Read part 3.