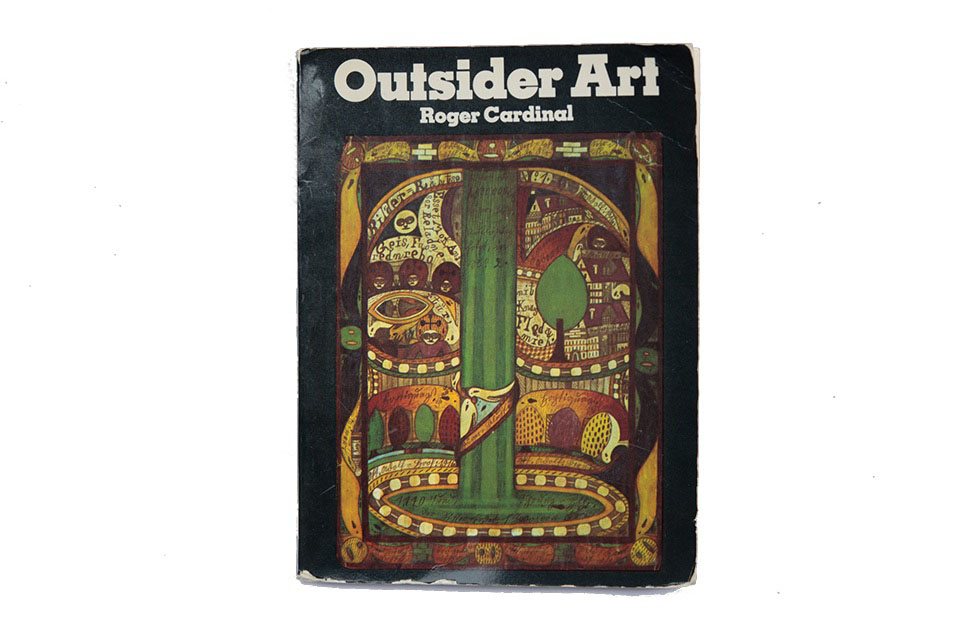

Roger Cardinal’s book “Outsider Art” (1972). The front cover artwork is by Adolf Wölfli

How to show – What the viewer takes away from each exhibition

Roger McDonald: In your book “Outsider Art”, more than half of the total pages are devoted to the artist’s biographies placing a strong emphasis on this aspect.

Then what about in the exhibition? What are the backgrounds of the artists and the context in which the works were created? To what extent should this biography be shown in the exhibition with the work? There are strong beliefs that the artist’s background is not necessary for appreciating the artwork, but how were these biographies dealt within the exhibition of outsider art at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1979, after you published your book?

Roger Cardinal: We exhibited the biographies. However, a significant reference was the exhibition in Lausanne, Switzerland in the late 1970s that was based on the extensive body of work donated by Dubuffet. In order to obtain permission for the exhibition and to resolve copywrite issues, Dubuffet spent months negotiating with the local authorities. This resulted in a number of controversies and a successful exhibition.

The venue was a magnificent old castle with a huge barn. How would one show this kind of work in such an environment? In the dark castle, lighting was placed close to the artworks, giving them somewhat a sacred atmosphere.

McDonald: But the exhibition at the Heyward Gallery was held in a white cube space, wasn’t it?

Cardinal: That is correct. The Hayward Gallery had a larger and more flexible space than the old castle. I felt that in the Lausanne show they wanted to show so much work that it became too much for the space.

In the Hayward Gallery we were able have enough space between the artworks and also took on the challenge to show Madge Gill’s01 27-meter long drawing. By hanging this huge work from the ceiling, the viewer was immersed in the work because they could not see anything else but the work.

McDonald: What about the lineup of exhibiting artists? What are your thoughts on the development of outsider art, for example, as seen in the 55th Venice Biennale02 in 2013, where modern and contemporary artists were mixed in the exhibition with outsider artists?

Cardinal: I believe that this method of integrating different expressions into the exhibition has already been thought of and explored by the Surrealists. The Surrealists organized exhibitions that included both famous and unknown artists, and other art forms such as cave art and environmental art. These experiments made it possible to view art in a new way.

By placing works by Henri Michaux03 and Salvador Dali04 next to Pablo Picasso’s,05 viewers were able to sense that “something is happening now.” Paintings started to speak to each other, and Surrealism overlapped with other expressive movements such as Art Informel and outsider art.

McDonald: Indeed. If you think about it, the same ideas can be found in movements like the Der Blaue Reiter06 in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. They also made exhibitions that mixed different art forms including contemporary art, folk art, paintings by children and mental health patients. The blueprint of what is happening now was already laid out a hundred years ago.

To view art is taking down the fence as a bystander and becoming a critic

McDonald: You mentioned earlier that the “viewer was immersed in the work” of Madge Gill at the exhibition in the Hayward Gallery.I was wondering what your thoughts are on “viewing art.” How do you access the artwork?

Cardinal: When I face an artwork, the first thing I feel is the urge to write. Do you keep a diary? The act of writing down about the art you experienced each time makes anyone a critic. You have to derive words that describes and expresses how you felt.

McDonald: You are saying that the job of the critic is nothing special.

Cardinal: That’s right. How did you feel and what did you think about in front of that work? What’s important is to derive words that describe that special feeling and to understand it yourself. “Intense” is one of my favorite words to describe outsider art, but when you are confronted with an artwork that evokes this “intense” feeling, it is impossible to perfectly express in words the emotions that arise. But can you, in third person, write down those feelings on my behalf?

What I mean by “intense” here is about the focus in the artwork. Outsider artists don’t just sit back in their chairs and say: “I’m finished for today, I’ll work on it tomorrow when I’m more relaxed.” If the viewer is not immersed in the chaos of creation, they will not be able to understand the work and not even about themselves. And many viewers are very timid about expressing such ideas in their own words.

McDonald: In other words, taking down the fence as a bystander and to becoming a critic is what viewing art should be.

Cardinal: Exactly. When the viewer is truly involved in viewing the work, there can also be risks. The risk of identities, egos, and what you believe to be destroyed. For example, in the artist’s world, all the practical troubles of our world are suspended. If we enter this world, we can look back at the real world and judge its flaws from there. Or you can feel satisfied about it. I use the word “intimacy” as a mirror of “intensity.” It is a word to represent the true entry into a world you have chosen to live in and one that you can change.

Outsider art is about creating a different world and letting us know that there are multiple realities other than this one.

Adolf Wölfli created an alternate universe that is not part of this world. What a courageous attempt that was. As you approach Wölfli’s world and find your words, in a sense you are collaborating with what the artist is trying to accomplish.

But you yourself are not present in his mental space. You are projecting yourself into his work. If you have a sensitive imagination, you will be able to see what is going on beyond the aesthetics of colors and form.

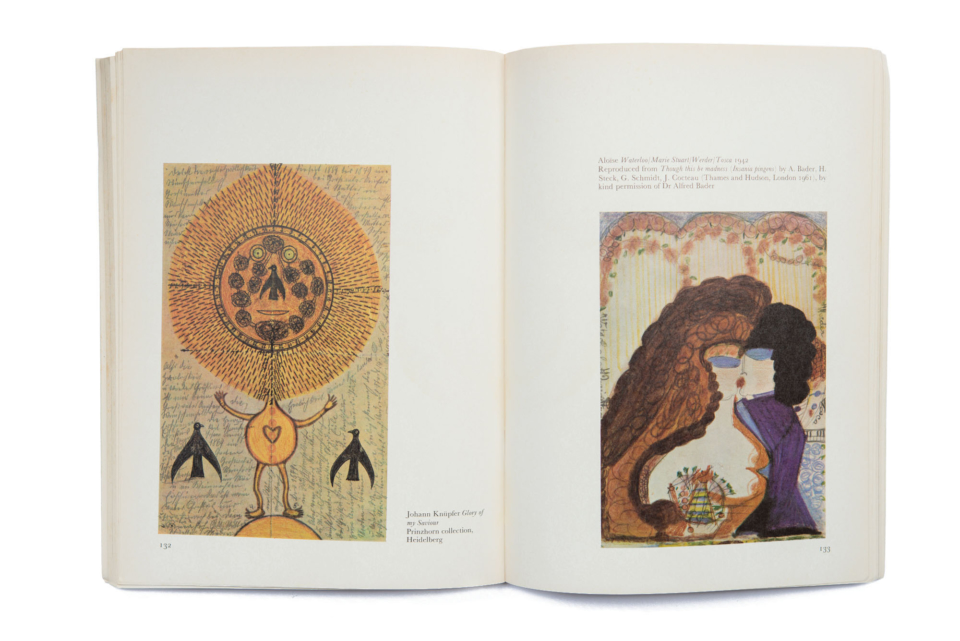

Think of the paintings by Wölfli. “That face” is at the center with patterns filling the space around it. The symmetry in Wölfli paintings are not the result of conventional training, but an explosive, violent, blood-gushing miracle. It is what he possesses spiritually laid out on paper.

Viewing outsider art means that you are on the verge of your own revelation. You debate about it, and you get frustrated at its peripheral, constantly searching for pieces of a world that is never fully explained.

Viewing art is to find the "blind spot" that exists in every work of art.

McDonald: Laying down on physical materials like paper what you spiritual possess. I think a good reference to this is traditional ink paintings of the early Song Dynasty in China. The relationship between mind and energy, and between hand, ink, and paper was highly theorized by the Chinese people practicing this style. This relationship between the mental spiritual state and the material output is evident in the ink paintings of this period. It was very important for these artists who lived more than a thousand years ago.

Cardinal: Indeed. Photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson07 also addressed this issue. He was interested in the “decisive moment” or the coincidental meeting between the sprit, eye, and elements in the space.

McDonald: I believe that the artist’s spirit continues to emanate from visual works, such as paintings. It is an animistic understanding that art is a material that harbors the spirit.

Cardinal: That’s exactly right. Our conversation has mostly focused on the “occurrence of words.” Picasso was probably the first artist we didn’t know how to talk about. Nevertheless, it was possible to grasp Picasso through words. The same is true of David Hockney. Both were also able to tell us about their paintings.

But even then, no matter how much we know about the artists and how much they talk about their work themselves, I feel that there is something in Picasso and Hockney’s paintings that is always overlooked. In outsider art, the artists say very little, and we have to start from the beginning. To look at their work also means to find something from what has already been overlooked.

McDonald: I suppose we can call this a “blind spot.” Even with famous artists such as Picasso and Hockney, if you look deep enough into the work, a blind spot is bound to appear. I feel that this points to the fundamental experience of viewing art.

Cardinal: Yes, that’s very nice keyword. A lot of things take place in this “blind spot.” There are hidden characteristics that are not visible on the surface. There is a second and maybe even a third meaning. You must be prepared for a journey to find these things.

McDonald: Lastly, outsider art is once again becoming popular in many parts of the world, including the Museum of Everything08 in London. As a result, the prices of artworks have skyrocketed, and the market seems to have become huge. What do you think of this?

Cardinal: In a sense, there is really nothing that can be done to protect outsider art from such external factors. But no matter how things change around it and even if it gets crushed by an overgrown market, it will always revive.

Everything that surrounds us can be damaged in one way or another. When we recognize that everything on earth is equally fragile, nostalgia is felt for what has been lost and what is left. This planet is also destined to be destroyed one day.

McDonald: I am pleased to conclude this conversation on such a cosmic note. Thank you very much.

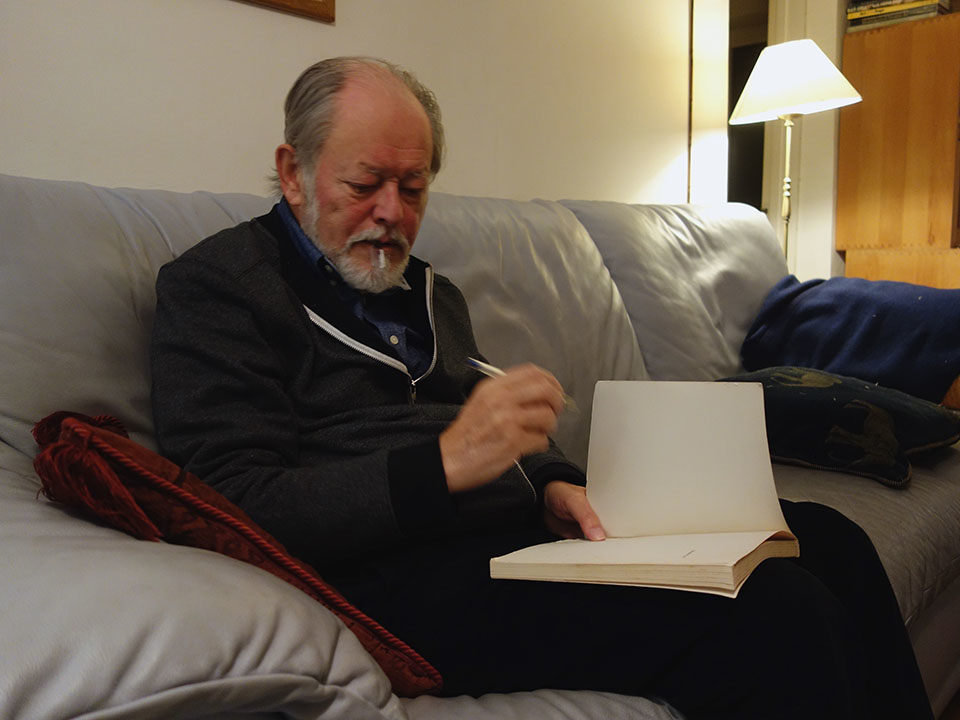

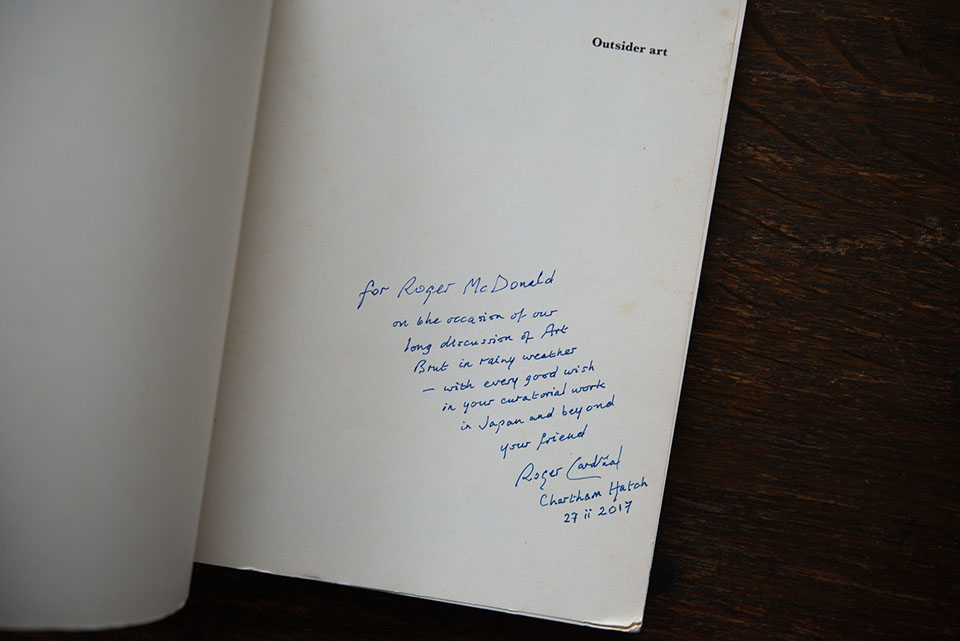

*Interviewed on 2017