Art by Accident

Cut through a length of unbleached cotton yarn with a pair of scissors, then knot the ends together. Snip through the yarn again, right at the center point between two knots, and knot the ends together again. Repeat until he has a length of yarn with knots at around 5 mm intervals along its entire length. Wind this into a neat, palm-sized ball of knotted yarn, and his work is done. To an outsider, it looks like a dauntingly lengthy procedure, but NISATO Chikara has done it every from 2008.

It began with a group atelier project using natural dyes. Everyone was assigned a different stage in the process, and Nisatowas in charge of winding the dyed yarn into balls for sale. Sometimes, during the rolling process, there would be an accident and the yarn would get tangled up. When this happened, there was no choice but to cut it and knot the ends together. Nisato, it seems, came to enjoy this procedure more than the winding. Before long he was cutting and knotting even untangled lengths of yarn, waiting until no one was watching to make his move.

‘The staff told Chikara to stop it, because when he cuts and knots the dyed yarn it can’t be sold any more,’ says ITAGAKI Takashi, Art Director at the 〈Lumbini Art Museum〉. ‘He said “Sure, sure, sorry,” but he didn’t stop, so they just let him do what he wanted. And now he does this as a job.”

Don’t his eyes get tired? ‘Apparently not,’ says Itagaki. ‘Really! He does this from 9:30 to 12:00, breaks for lunch, and then gets right back to it in the afternoon. Every single day.’

Nisato’s eyesight is weak. On cloudy winter days when the light is bad, he takes the arm of a staff member when walking from place to place. In order to make the undyed yarn he works with more visible, he bought a black-topped workbench at the furniture store. The workbench also has shelves to store yarn, making it ideal for his purposes. The collection of yarn winders and skein holders he keeps in his workspace gives it a cool near-future feel.

As Itagaki and I speak, Nisato sits hunched over beside us, fingers so close to his face they almost touch his nose, carefully tying knots one by one. His concentration is so intense that he ignores other atelier users who try to engage him in conversation, even if they touch his face. Watching him cut and knot the yarn, I am reminded of the repeated separations and reunions of cell division. It’s as if the straight yarn we usually see is the old version, and Nisato is helping it evolve into a new form.

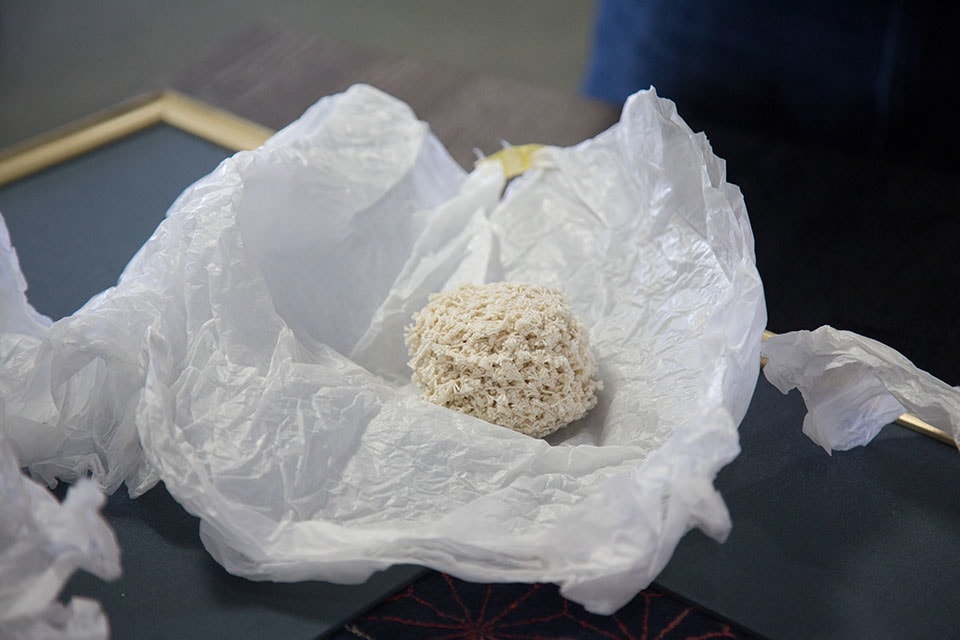

Nisato’s finished bundles of wound-up yarn, bristling with knots, combine the delicate beauty of an assemblage of tiny petals with the cuteness of a baby animal. When I ask permission to hold one, I am surprised to find it heavier and tougher than I expected.

The Joy of Cutting and Tying

Nisato’s works have been displayed in many exhibitions, but they all share the same title: 《Untitled》.

‘Calling them all 《Untitled》is a bit odd, I know,’ says Itagaki with a rueful laugh. ‘I once asked, “Chikara, what is this?” “Yarn,” he told me. “It’s yarn.”’

Nisato himself does not think of these untitled balls of yarn as works of art. He just enjoys the cutting and knotting, without concerning himself about what happens to the material later. Once, when another atelier used one of the balls as material for weaving, Nisato was unperturbed. ‘That’s fine,’ he said. This easy-going nature has made him quite popular with the ladies, too.

In one corner of Nisato’s workbench I see a framed photo of a white dog.

‘Very cute,’ I ask. ‘Is she yours?’

She was the dog we had at the facility explains Itagaki on Nisato’s behalf. ‘Chikara used to feed her and look after her. The dog loved him, and he loved her too. . . That’s right, isn’t it, Chikara?’

Itagaki peers into Nisato’s face for confirmation, but Nisato doesn’t take his eyes off the yarn for a minute. ‘Right,’ he says, pulling another knot tight.