Understanding and Admiring the Extraordinary is Also Art

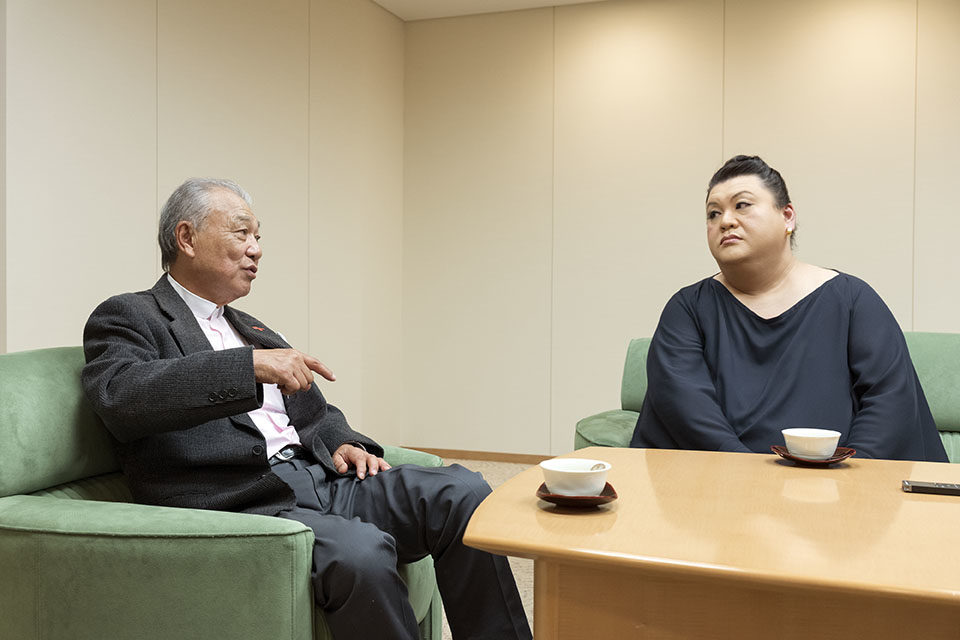

The Nippon Foundation building in Akasaka, Tokyo, houses both The Nippon Foundation Paralympic Support Center and an office shared by different Paralympic national sports federations. The center was founded with the aims of contributing to the success of the 2020 Tokyo Paralympic Games and promoting Paralympic sports in general. The venue for this conversation was a familiar one for Matsuko Deluxe who serves as adviser for the center. Looking at some of the art collection of The Nippon Foundation, they started the discussion by first sharing their thoughts on art created by people with disabilities.

Matsuko and Sasakawa look at some 40 artworks from the 622 pieces in the collection acquired by the Nippon Foundation after the exhibition “Art Brut Japonais.”

Matsuko: People think of me as unsophisticated, but I actually appreciate art. When you are busy with your everyday routine, it becomes harder to get excited about anything. But art is able to move me in very simple ways. For example, there is a social welfare facility called Nemunoki School, founded by actress MIYAGI Mariko, who set aside time for its residents to engage with creative activities like painting. I first became interested in their creative endeavors through watching a TV documentary program about the facility. There is an artist who still lives there and paints pictures I really like. I think his name was HONME Toshimitsu. All of his paintings are so pretty.

Sasakawa: The work of artists with disabilities has a naïve allure. For many of the artists, it’s really not about their ego, such as making artworks in order to look important or become famous. You say that looking at Honme’s work, you were sincerely touched regardless of the artist’s name or background and his work profoundly moved you. While this is what art is really all about but it is difficult to encounter art in such a way because we often look at and judge a work of art based on the name and other information about the artist.

Matsuko: It is true that the moment we recognize the name of a famous artist, we tend to automatically get excited. But when I was shown the work of someone like Honme who doesn’t have any acclaim, it was different. This made me realize how superficial my previous experiences of art were.

Sasakawa: Because the work of these artists come in the purest (simplest) form of expression it is a challenge for the viewer. But this fresh stimulation is precisely what you gain from seeing art made by artists with disabilities. The Nippon Foundation’s collection comprises 622 of their artworks. Today, I very much wanted you to see some of these works from our collection.

Matsuko: How did you collect such a large number of artworks?

Sasakawa: Well, it all started when the foundation provided a grant for the “Art Brut Japonais” exhibition held in Paris from 2010 to 2011, showing the work of 63 Japanese artists with disabilities. The exhibition aimed to give these artworks aesthetic value so that eventually the word “disability” would be recognized positively in society. The show was a great success, so much so that it was extended beyond its original closing date. We decided to acquire 70% of the artworks exhibited to ensure these valuable works would not be scattered and lost after the exhibition, and subsequently launched The Art Brut Support project.

Matsuko: Collecting works of art also involves the task of finding extraordinary talent. This isn’t just philanthropy. It could ultimately lead to national cultural interest.

Sasakawa: I think so. At that time, there were not so many museums in Japan that exhibited and collected works of artists with disabilities. For that reason, The Nippon Foundation decided to preserve them under good condition and loan these works of art to suitable exhibitions. Since then we have supported the renovation of old traditional buildings to transform them into museums in various parts of Japan while also providing ideas for planning and running exhibitions. Through our support for artist in social welfare facilities we came to learn that there are many special terms and concepts, “art brut” being one. Therefore, the project hitherto implemented was revised in 2017 as “The Nippon Foundation DIVERSITY IN THE ARTS” and we will continue to explore the potential of the project focusing on diversity in art activities.

SHIMIZU Chiaki (Atelier Yamanami, Shiga Prefecture) created an artwork using Matsuko as a model. Looking at the artwork which was displayed at the exhibition organized by The Nippon Foundation DIVERSITY IN THE ARTS in October 2017. Matsuko said, “Wow! Is this me? She has made me much thinner than my actual size!” “She’s being careful not to offend you,” laughed Sasakawa. “She certainly is!” replied Matsuko.

Is Commercial Success a Good Thing?

Matsuko: Are artworks by artists with disabilities sold at art galleries?

Sasakawa: In general, people are cautious about selling these artworks commercially. Depending on the artist, though, some exhibit at art fairs overseas and are even bid at several thousand dollars.

Matsuko: I think it is not necessarily a bad thing that economic activities are incorporated into art. Think about Van Gogh. If he had sold his paintings when he was alive, even just one piece, he could have lived a little bit happier. I know some people would respond that Van Gogh was able to produce masterpieces precisely because of his miserable life. This is a difficult issue. But in general, I don’t want artists to have to worry about food or shelter. Even if “outsider art” becomes commercial to a certain degree, it is up to us who look at the work to judge whether an artist creates it for the sake of the market or if he or she has maintained their integrity.

Sasakawa: Artists create their work with pure intentions. It comes down to how people surrounding the artists accept and understands them, and responds. As everyone’s standpoint is different, there are a lot of complex issues involved.

Matsuko: We have to properly watch how this commercial aspect evolves. One thing I realized after looking at some of the artworks from your collection is that the people who make art, whether they are famous or not, are eccentric people compared to an average person like myself. And because they are person of unusual ability, they cannot even pretend to fit into society. It makes sense that art exists as a method for them to communicate their exceptional qualities.

Sasakawa: I agree.

Matsuko: YAMASHITA Kiyoshi, an artist famously known as the “Naked General,” is a good example. He uses the “chigiri-e” technique [a Japanese paper collage method of pasting tiny pieces of colored paper to depict an image] and the results are just extraordinary. He spent years finishing each work of art. The same thing can be said about the artworks you showed me just now. There is no way that I could possibly make something like that. Their art evokes a sense of respect and admiration. Thinking in this way, we have to ask ourselves what “disability” really means. In fact, it might be that it’s an “ordinary” person like myself who has the disability.

Sasakawa: That’s right. There is a Japanese proverb that says that everyone has faults or disabilities.

Matsuko: In society today, we say “people with disabilities” or “the disabled” based on conspicuous features that are easy to differentiate. Yet people without the so-called disabilities, including myself, are also dependent on society. Society takes care of all of us. But people without disabilities generally think as though they never rely on society. They forget that they, too, are dependent. I think art has the power to make people aware that everyone relies on one another.

I Hope that Someday the Word “Disability” would Disappear

Sasakawa: I think the categorization of people “with” and “without” disabilities no longer makes sense. In the first place, we all have different backgrounds, cultures, and ethnicities. We have also applied gender binaries, based on how we look, until very recently. If we classify people based on how they feel inside, as opposed to how they look, it is clear that we cannot classify people in such a simplistic manner. And this lies at the core of LGBT issues. If I analyze myself deeply I might also have about 10 % to 20% feminine traits.

Matsuko: Because it is not about all or nothing.

Sasakawa: In the end, everyone is different. While we have long divided ourselves based on various criteria, such as physical appearance, religion, and nationality, I think people have started realizing that we cannot no longer get along in society with this kind of categorization. That is why people have started using the term“diversity.”

Matsuko: Exactly. I think being different will no longer mean anything in the future. For example, it will soon be possible for a Paralympic athlete to jump further than an Olympic athlete due to advances in equipment. Incredible inventions will also be made, enabling people with physical disabilities to lead lives just like other people as the result of rapid technological developments. In such a future, the differences we used to consider as common sense will lose their significance. Eventually there will be tools that allow people who speak different languages to engage in conversation with each other . Then even national borders will make no sense. This is the direction that we are heading in. Just like what you previously said, people now doubt the conventional way of categorizing people based on their features. That is why all of the sudden, we started using the term “diversity” to articulate this new awareness. I only hope the term isn’t just a fad that doesn’t lead to real change.

Sasakawa: That’s the biggest problem. People understand the concept of diversity in theory, but tend to act differently. One of the reasons could be that our highly advanced culture today has deprived our lives of its warmth. In the past, for example, three generations lived together in the same house, and we had people with visual impairments as well as mental disabilities and the elderly in our neighborhoods and schools. A lot of people with different features lived side by side. With the development of suburban welfare facilities, however, we live today in segregated places, and the city is filled only with people without disabilities. I think we should start connecting people again.

Masuko: It is impossible for people to understand one another completely. But if, for example, you come to like an artist through art brut or an athlete through Paralympic Games, your notion of disability then changes and you might want to learn more about it. Learning about it is undoubtedly better than remaining ignorant.

Sasakawa: 2020 will be one of the opportunities where The Nippon Foundation Paralympic Support Center, of which you serve as advisor, is advocating to create a society where people with and without disabilities can live together equally.In other words,the consistent stance of The Nippon Foundation is that an inclusive society will be the legacy of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games. We are in the process of planning different approaches to achieve this goal.For example,we have developed a barrier-free map application called Bmaps that provides information related to accessibility to make it easier for a wide range of people such as for people with disabilities, the elderly, baby stroller usersand foreigners to be actively mobile outside their homes. We are now making a nationwide call for inputs of useful barrier-free information into the Bmapssuch as wheelchair-friendly restaurants or barrier-free hotelsand so on, with a goal of eventually covering one million locations.

Matsuko: No matter how much the Internet advances, you still have to have the will search online to find the destination. What The Nippon Foundation is trying to do in this context seems to be creating chances that stimulate people to do this.

Sasakawa: That’s right.

Matsuko: I think society has changed in the last 20 or 30 years. Cities today have more accessible toilets as well as better access for wheelchair users, which was unimaginable when I was growing up. I think 2020 provides a good opportunity to improve the cities even more. I’m sure there are many different ideals but what I want is simple. I want even just one more accessible toilet, one more wheelchair ramp, or one more facility accessible to the visually impaired and wheelchair users. For me, that should be the legacy, rather than building extravagant sports facilities.

Sasakawa: And it would also be good if the term “disability” will no longer exist. I don’t want to use it even now, to be honest. Likewise, a genuine diversity is realized when the word “diversity” itself is erased from our vocabulary.

Matsuko: Yes. Is there a better word we can use? Let’s keep thinking about it together.