As if to throw several doubts at fixed concepts

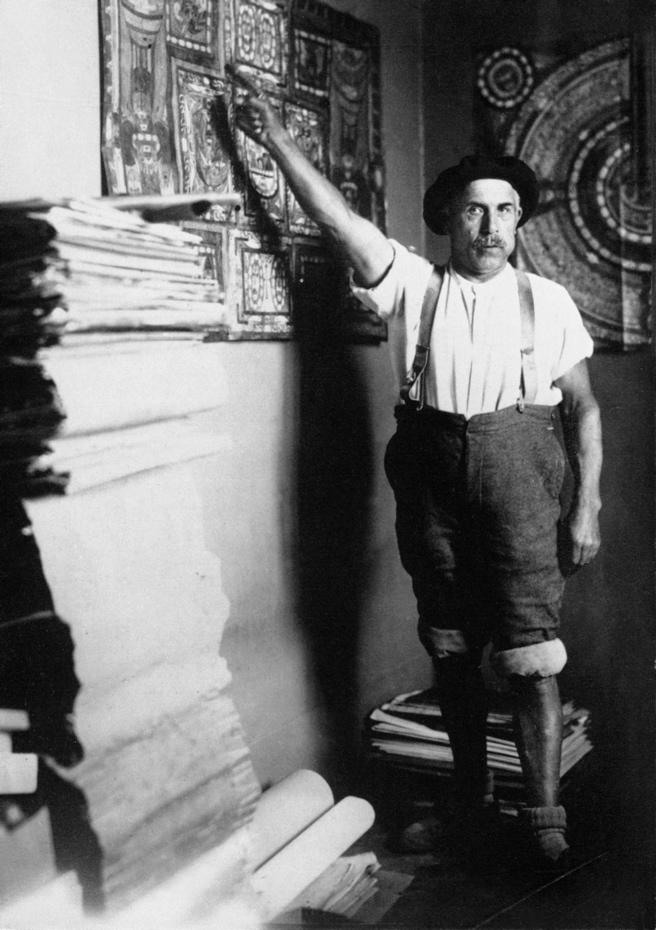

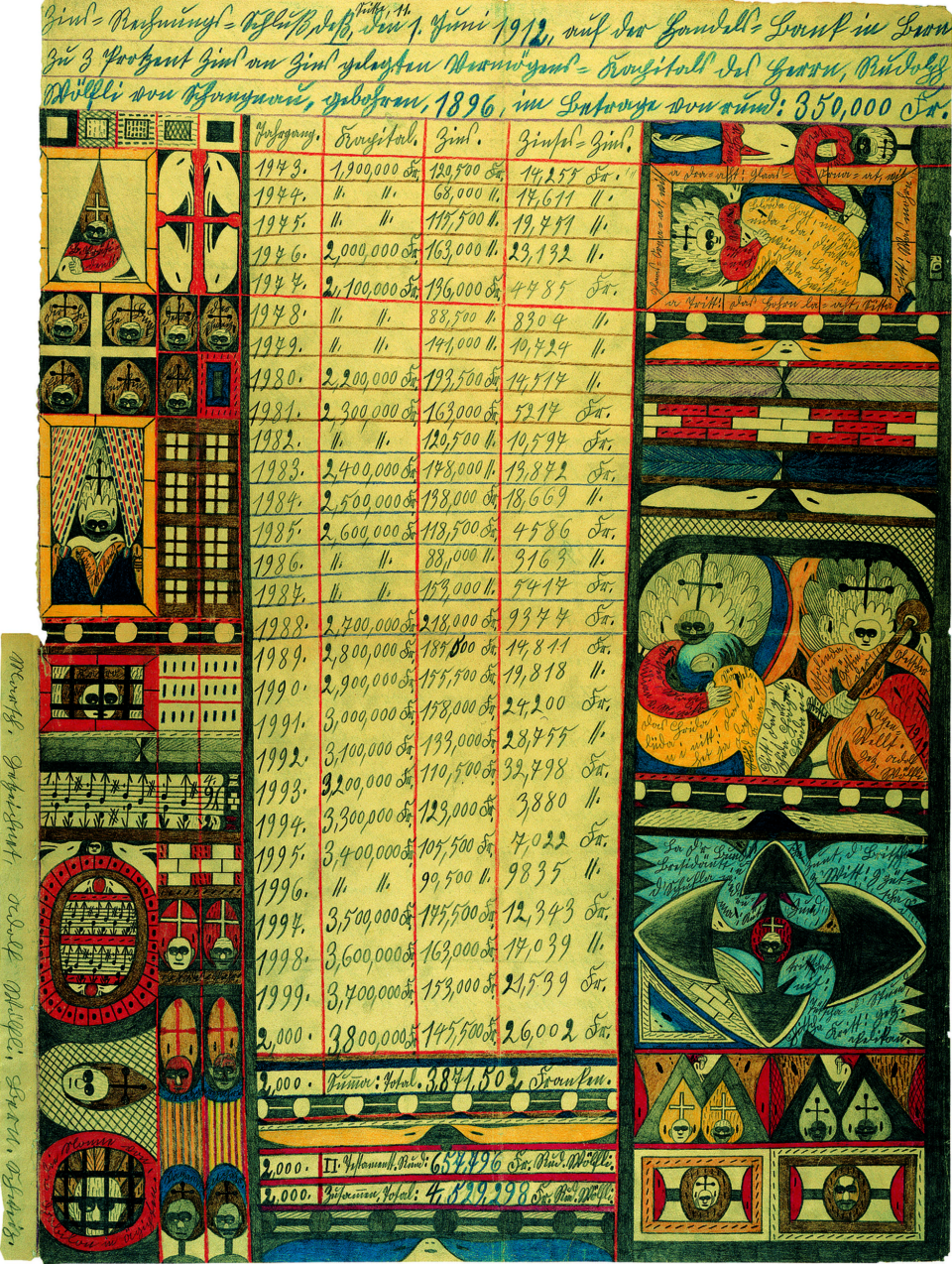

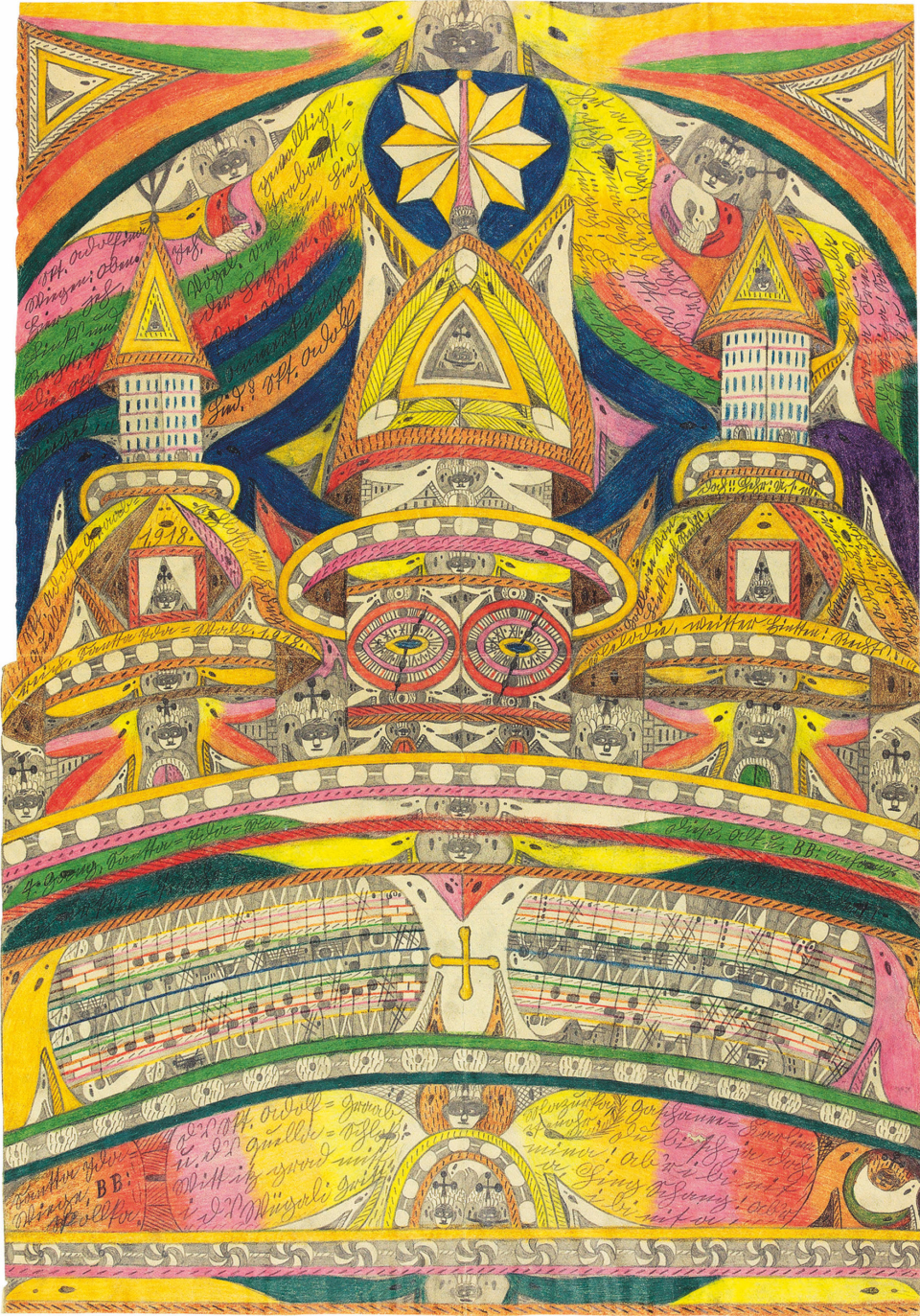

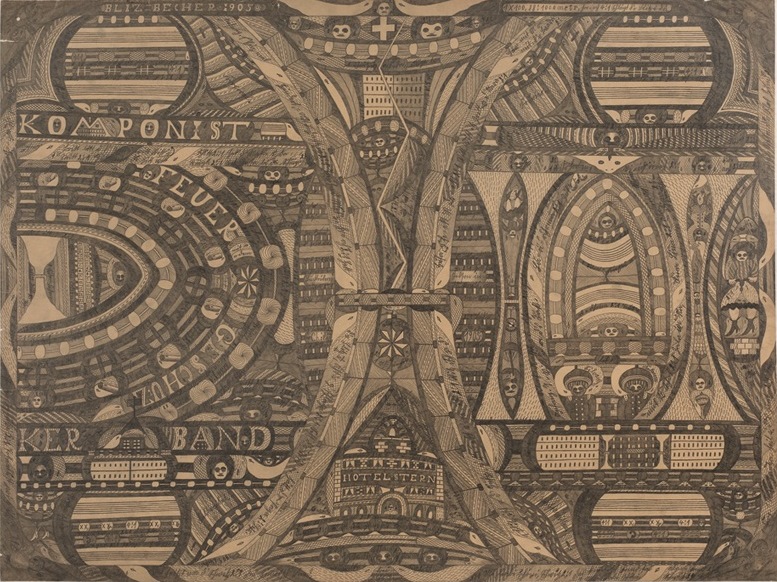

I’m looking at monochrome drawings made in pencil. Early Adolf Wölfli01 pencil drawings have lines that look like musical staves, words, drawings of people, and even the signature of the composer. In works made with colored pencils, the musical score is drawn evenly and rhythmically, and in these works the music seems as if it might be composed. The tightly woven text might be written as a sort of lyrical poetry. Numbers fill a page like a spreadsheet, reminding me of densely packed information seen in computer programming calculations. Perhaps this music could be performed, perhaps this poetry could be read aloud, perhaps these calculations could be used as a computer language. It begins to look like a medium that allows me to imagine many possibilities.

I read his enormous story further. I begin to think that by engaging in his creations, they finally become works of art through our imaginations. By this I don’t mean that his work is incomplete or missing something, but that by being close to his work and engaging with the work in a cooperative way, a sense of “living art” comes into being. For us to begin to do this, it is important for us to remove our fixed assumptions. In other words, for example, we discard the frame that is Outsider Art02/Art Brut,03 and discover an extremely strong originality. Through this method, I see how his many approaches to his work blend together in complex ways, and I get the sense that this is meant to teach us that there is not one single truth, but countless truths. It is as if he is throwing several doubts at the conventional perceptions that we have internalized.

©Adolf Wölfli Foundation, Museum of Fine Arts Bern

©Adolf Wölfli Foundation, Museum of Fine Arts Bern

The White Space of the Score, and the Holes Leading Inside

Here, I listen to some of the music. Belgian composer and violinist Baudouin de Jaer has interpreted Wölfli’s artwork into a score and recorded his performance on an album released by Sub Rosa, a music label based in Brussels. At times the violin plays a harmonious melody, and at other times the high-pitched tones stabbing at my eardrums don’t sound like a violin at all. The music sounds more like the percussive rhythmic calls of animals or bugs. I am aware that I am listening to music, but perhaps this is because I know that I am hearing a recording based on Wölfli’s score, so my ears are expecting to hear music. However, if I didn’t have that information beforehand, it would seem less like music and more like I am simply listening to sounds. It seems to move back and forth between music and sound.

De Jaer unravels Wölfli’s work. He reads the rules, structures, and instructions within the score, and transposes them to his instrument and converts it from a picture to music. This act is close to getting near to Wölfli’s work, and imagining something new. By collaborating with Wölfli’s work, it becomes music that can be performed in the real world. I think the majority of people have a Western way of thinking about music, where the sounds are harmonic and orderly without any divergence. When I listen to this album, I begin to feel that music doesn’t have to be what people have decided it is. All we need is for sound to be there, and we can enjoy that the disorderly notes are played in a pleasant way. The so-called musical score is complete with notes and instructions; it is absolute. The composer has certainly written a world of sound, and we must present it exactly the way the composer imagines.

However, there is a sense of white space somewhere in the notes of Wölfli’s score. At first glance it seems the work is packed with motifs and there are barely any spaces, but when it is played, spaces appear in the sounds. What is this white space? Wölfli’s work has many human faces and eyes in it. There is a sense of a sharp gaze peering out, but in fact the eyes are drawn like black holes. These are not eyes, but I imagine they might be holes that connect to the inside of the work -holes that connect to the inside of Wölfli. Perhaps we could call it an interface that connects us to the work. I feel as though these holes appear in the music as “empty space.” It is easy to feel that the sounds are appearing naturally from the score. The music is live, raw truth, and even wild. This is at the same time music, a story, a lyrical poem, and a picture. Wölfli’s work seems to be all of these things.

©Adolf Wölfli Foundation, Museum of Fine Arts Bern

What We See is Not Just a Single World

Through encountering the massive volume of his work, I get a certain sense of time. That is, the time Wölfli spent over many long years creating this work. This is the history of one human being who fought to continue releasing his work as something both individual and social, personal and strange, ordinary and the extreme opposite. I sense an incredibly ambiguous world. His work helped me realize that the world we experience every day is not a single world, but that there are other unseen worlds that may exist. This is what I found myself thinking as I encountered Wölfli’s incredibly individual mythology.

all works and photos ©Adolf Wölfli Foundation, Museum of Fine Arts Bern