Finding the Original Form of Geinō on the streets of Africa

KAWASE Itsushi

Born in 1977 in Gifu Prefecture. Engages in anthropological research on African music culture, and creates ethnographic films. From the intersection of anthropology, cinema, and contemporary art, he cultivates new ground for expression. In 2016, as guest professor for the University of Bremen, Shandong University, and Mekelle University (Ethiopia), he held intensive lectures on the theories and practices of visual anthropology. He also co-authored and co-edited Afurikan Poppusu!– Bunkajinruigaku Kara Miru Miwaku no Ongaku Sekai (‘African Pops!—The Captivating World of Music from the Point of Cultural Anthropology ’)(published by Akashi Shoten) and Field Eizo Jutsu (‘Film Techniques on the Field’) (published by Kokon Shoin), among others. His most prominent works of film include Lalibalocc – Living in the Endless Blessing-, Kids Got a Song to Sing, When Spirits Ride Their Horses, and Room 11, Ethiopia Hotel (winner of the “Premio per il film più innovativo [Most Innovative Film]” award at the Sardinia International Ethnographic Film Festival). He is currently in the process of editing a film about the creation and passing down of the folk songs of Tokushima Prefecture and the nursery songs of Gifu Prefecture.

http://www.itsushikawase.com

Fieldwork in Ethiopia

The field of “visual anthropology” of which I am a part, is a field of anthropology that explores audiovisual storytelling—in capturing cultural phenomenon, including people’s everyday lives, onto film. This isn’t to say I always aspired to academia; in fact, I spent most of my student life playing in a rock band, living a life as a musician. During that time I went backpacking with my guitar, jamming with a variety of musicians on streets all over the world, and when I studied abroad in Vancouver, I performed in bars and restaurants. The cultural anthropology program and indigenous peoples research program at my host school, the University of British Columbia (UBC) was well-established, but at the time I didn’t think at all that I wanted to be an anthropologist.

Vancouver, however, with its many immigrants, is home to people of a vast variety of ethnic groups. And as I interacted with these people in my daily life, I was able to understand through experience the lifestyles and ways of thinking of a variety of people. By being able to understand diversity in the physical sense, as something felt instead of read about in a textbook, I found myself gaining an interest in anthropology. After that, I attended graduate school at Kyoto University and went to Africa, for the first time in my life, to conduct fieldwork. I went to Ethiopia with a guitar on my back, like it was an extension of the backpacking trips of my past. The people around me said I seemed more like a hippie than a researcher.

My home, built for me by the villagers. In the outskirts of Gondar, Ethiopia.

Capturing on Film the Entertainment within Everyday Life

The country of Ethiopia, with an area about three times that of Japan’s, is home to over 80 ethnic groups who in total speak over 100 different languages. In the northern Amhara region of this multi-ethnic country is the ancient city of Gondar. Once the capital of Ethiopia, it is a city where art culture blossomed. There, I encountered two music groups, the “Azmari” and “Hamina (or Lalibela)”. The Azmari, once court musicians for royalty, sing and play the masenqo, an instrument composed of a horse tail string and a soundbox covered with goatskin. The Lalibalocc on the other hand, do not carry instruments, instead traveling in groups and singing in front of houses. They provide the people with words of blessing, and in return are given money and food. This is very similar to the “kadozuke” culture that once existed in Japan, wherein street performers would perform in front of the gates of people’s houses and paid money in return for entertainment.

Azmari musicians of Ethiopia in 1936, photographed by the Italian Army.

(Left) An Azmari holding his masenqo instruments in Gondar, Ethiopia.

(Right) Practicing the masenqo as a student conducting research in Ethiopia.

The Hamina do visit houses to beg, but before they begin singing, they first conduct a kind of research in the town to gather information from neighbors about the people from whom they are begging and change the verses depending on, for instance, the listeners’ religion or occupation. They try to uplift the feeling of listeners with praising poetry —“you’ve succeeded in your laundry business and built a fortune; you are a wonderful person under the divine protection of God”—and invite charity. But the villagers are not to be taken lightly as well, dodging their requests by claiming they don’t have time, or that their parents aren’t around and they have no money. In this interaction there is bargaining, but also lies. The Hamina’s music exists to provide a flourish to these gritty interactions on the street. In this phenomenon I felt as if I saw the original form of Geinō in Japanese sense, deeply rooted in everyday life.

It is possible, of course, to analyze from a musicology perspective the scales and harmonies that make up their performances and songs. Though I think this could be a meaningful endeavor to focus audio-visually on the singers’ creativity, by specifically centering on the use of rhetorical expressions in interactions with the audience.

The Hamina, who go around singing together at each individual house.

Lending an Ear to the “Local Yardstick”

When we try to understand art, we often depend on modern Western standards to discern its value. For instance, there is the general belief that music is something that musicians use to express themselves, the manifestation of a free spirit. In northern Ethiopia, however, music is thought to be “a gift from God,” and is not considered an individual form of artistic expression. Other than the music used in hymns and rituals for the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, which wields great influence in the north, the belief in Ethiopia has long been that music for the common people should be entrusted to specialized musicians. These musicians are not artists but craftsmen—in a local word, “Muyatenna.” Music used to be considered a skill, passed down for generations, and also mark these people as part of an outcast group within society. What is important for these people is the extent to which a singer can make the listener feel good and lift their spirits. This is a standard that does not coincide with how we discern value in one’s singing, which is often by evaluating the singer’s tone of voice, or the steadiness of their pitch. A song that, to us, sounds like something by a tone-deaf singer, is considered a good song for them if it moves the listener and invites charity. In this kind of situation, the simplistic standards that we use to evaluate music in our everyday lives – “low / high musicality,” “good / bad” – cannot easily be applied. In other words, we must re-evaluate the framework we use to understand art and expression, shatter it lightly with a hammer, and lend an ear to the “local yardstick,” the local standards. I feel that our research, while building this new framework, is also meant to continuously question how it should really be. In that sense, I feel I have only just begun to understand the music culture in northern Ethiopia, and that there is no real end to this process.

With future clergymen, a group of Ye'kolo-temari.

In this way, there are a vast variety of “yardsticks” throughout the world, but personally, I have always believed that there is no need to rush to bridge the gaps between them. There is no need for people of completely different cultural backgrounds to understand each other instantly, and indeed, they may not be able to do so. Instead of thinking, always, that the difference in our understandings is something negative, something to be fixed, I believe we should stop, observe carefully, enjoy the differences, and think for ourselves about each other. As a visual anthropologist, my goal is to record this process of communication, support it, and reflect it in my research activities.

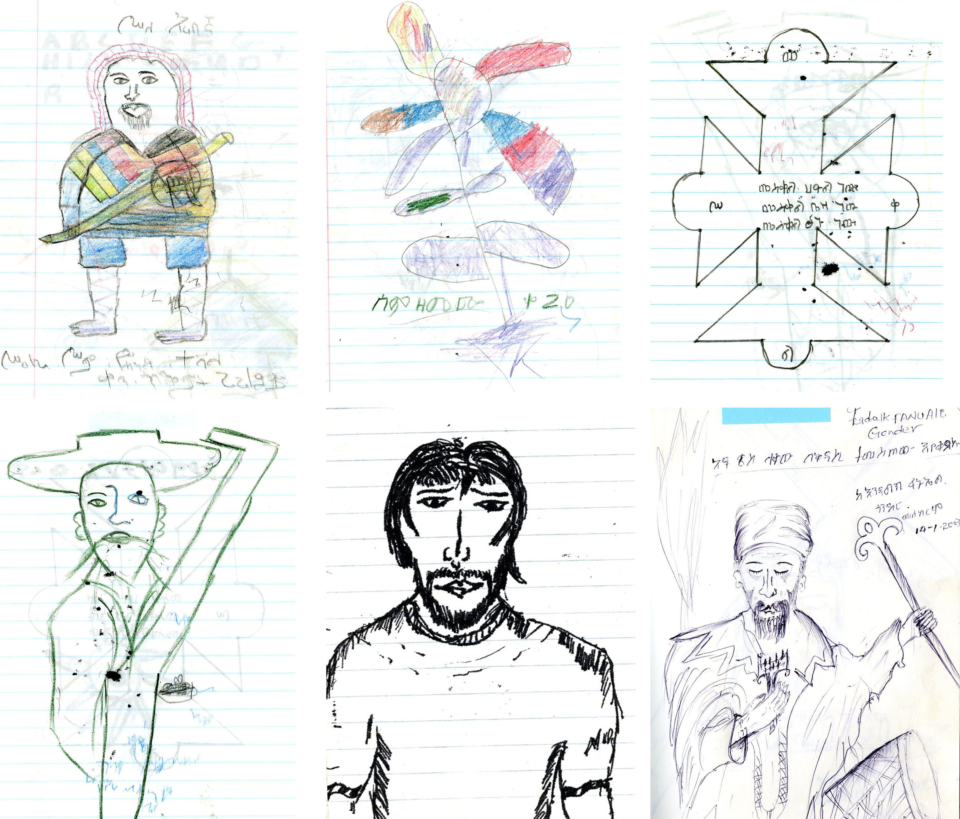

Field notes that Mr. Kawase used in his Ethiopia research, with doodles by local children.