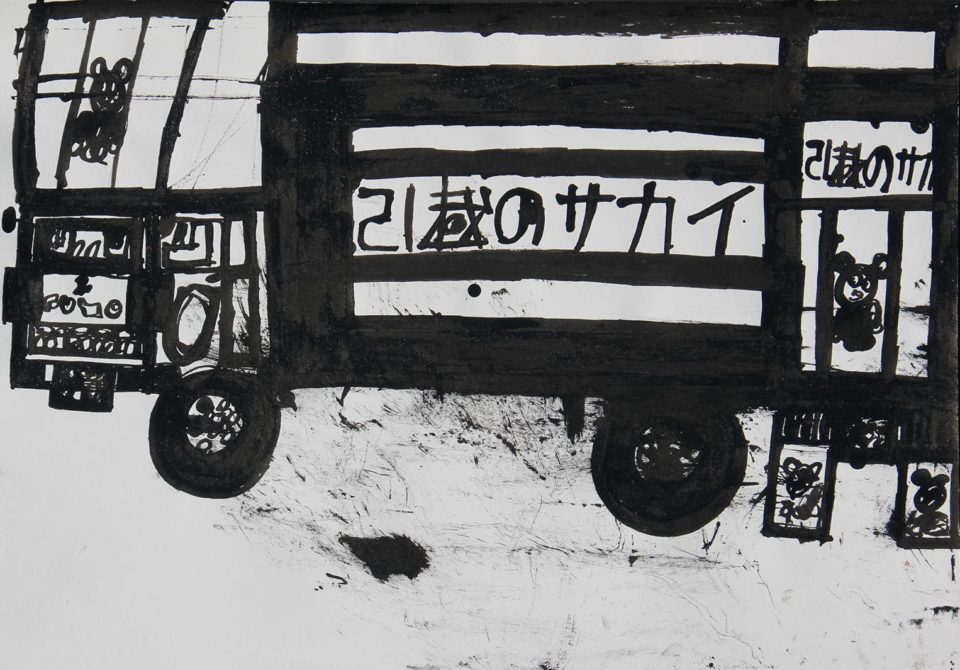

Anpanman1 and Trucks and a Chopstick and…

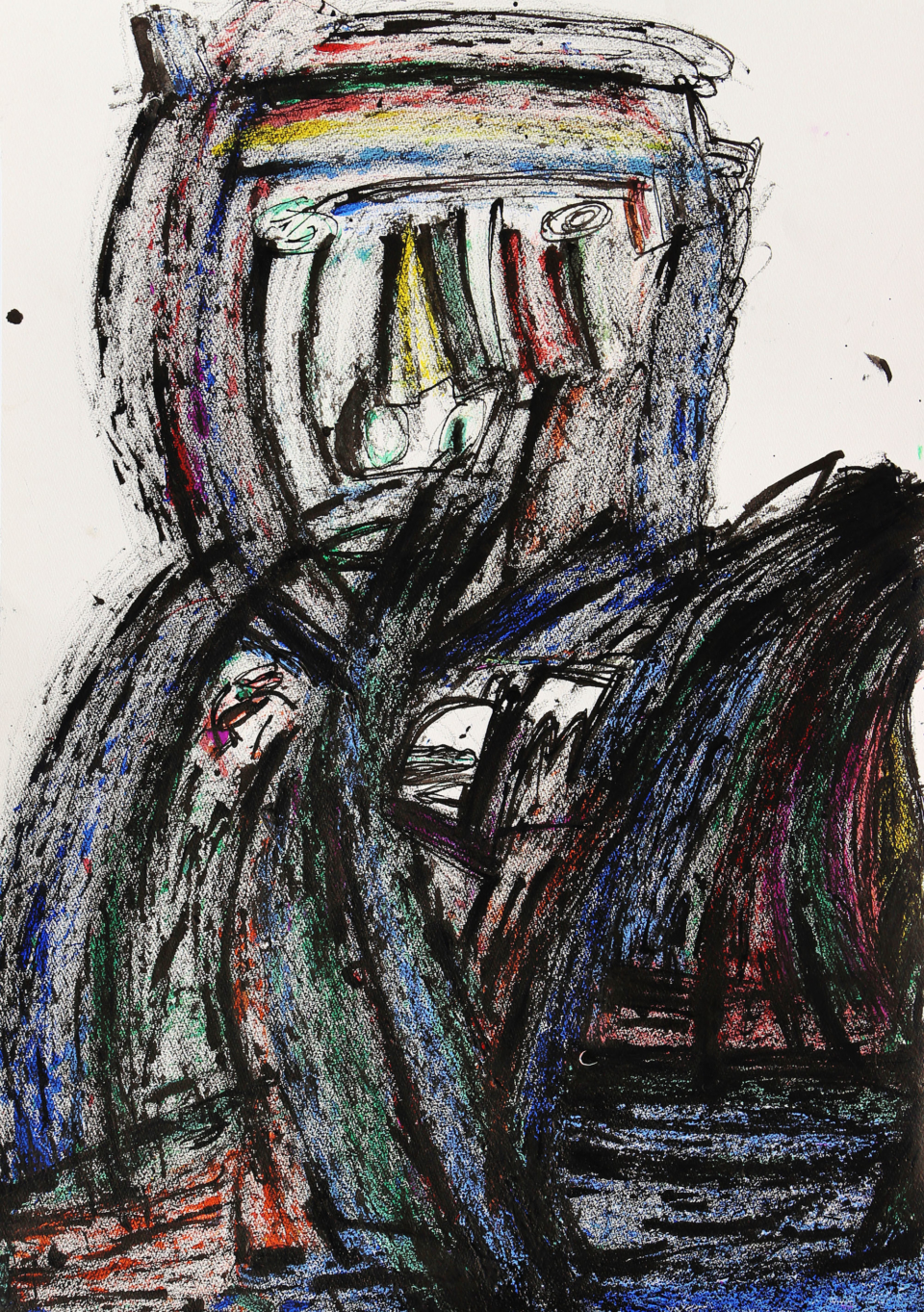

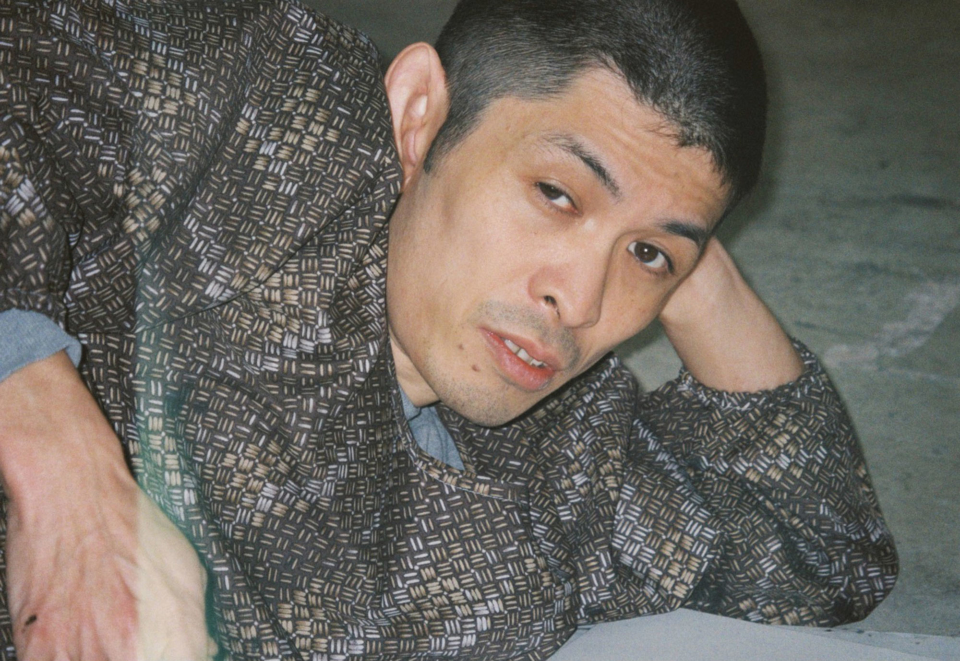

Music is playing. I open the door and see a man drawing in the middle of the room, propped up on the floor on one elbow. He dips a single disposable wooden chopstick, or waribashi, he is holding into a bottle of India ink and slides its inked end vigorously over the white drawing paper. Ink drops splatter on the paper, around bold, confident lines. How much of this is intentional? It seems at first as if he is sliding chopstick over paper carelessly, without thought, but as the lines rubbing against one another become more concentrated, a face begins to emerge. He draws again and again over lines he has already drawn, capturing the flow of it all. The man’s name is Toshio Okamoto. Mr. Okamoto, who is autistic, has been a member of ATELIER YAMANAMI since 1996, and began drawing in this style 10 years ago.

岡元さんが、ねころがりながら絵を描いている様子

“The first 10 years, Mr. Okamoto couldn’t hide his frustration,” says facility director Masato Yamashita, who has been watching over Mr. Okamoto since he first joined the facility. “We’d noticed that he didn’t like being bothered by anybody, and kept trying to think of ways to make his life here more peaceful. We tried this and that but nothing seemed to work, until one day we took him out on a drive. We noticed that he was very interested in the truck on the road next to us, so we prepared some drawing materials and encouraged him, just casually—why don’t you draw a truck? And he started drawing, one after another.”

Ever since, Mr. Okamoto keeps his eyes peeled for trucks whenever he is on a drive, etching into his mind everything from their fronts, sides, and backs, and then draws detailed pictures of them with India ink and a waribashi.

Being His True Self

ATELIER YAMANAMI provided him with a private studio, so that Mr. Okamoto, who dislikes being around others, could draw trucks in peace. This is also a part of ATELIER YAMANAMI’s firm belief in creating an environment for each and every member, where they can do whatever they want andhowever they want. This can inlcudeeverything from clay modeling, drawing, embroidery, to sashiko (traditional Japanese embroidery). Apart from Mr. Okamoto, the workshop is host to many members engaged in a variety of artistic endeavors. The pieces they create are displayed at Gallery gufguf, which is attached to the workshop, and also exhibited domestic and international galleries and art museums.

“Mr. Okamoto, when he’s concentrated on something in his private space, draws and draws and doesn’t even leave to go to the bathroom. Other than that, he sometimes writes a word he likes on a piece of paper, and brings it to the staff to communicate with us. And other times,” says Mr. Yamashita, laughing, “He’ll just fall asleep while he’s drawing.”

岡元さんが、ねころがりながら絵を描いている様子の写真

Bob Marley, Miles Davis, Stevie Wonder, Audrey Hepburn—having recently taken to drawing people, it takes Mr. Okamoto about two weeks to complete one drawing. What strikes me, as I look through these drawings, is that not only do they capture firmly the shapes of each face, they seem simultaneously freed from these shapes by a supple individuality. It is in these elements that I catch glimpses of his genius.

“People tell us it’s good that after 10 years, Mr. Okamoto’s finally been able to relax. But I personally can’t think of it that way because, on the flip side, I regret that for 10 years we weren’t able to understand him. ‘Let’s sit down and draw.’ ‘Let’s turn the music down a little.’ ‘Let’s draw with everyone else.’ We’d given him all these conditions and restrictions. And now, finally, we’ve reached a situation where Mr. Okamoto can be his true self—in this room by himself, drawing on the ground, listening to the theme song of “Anpanman.”

What Mr. Okamoto’s intent is in drawing these pictures, we do not know. This is why the viewer is challenged all the more when looking at the pieces, because they need to decipher what is in front of them with their own words, their own emotions. “Anpanman!” Mr. Okamoto’s voice echoes through the room.. Ashamed of myself for not being able to express in words the liveliness, the magnificence of his art, I can only yell back “Anpanman!”, putting all trust into this animation character to convey my feelings.

*Anpanman is a Japanese superhero picture book and anime series originally written by Takashi Yanase starting in 1973. Particularly the theme song for the anime series, which started broadcasting from 1988 and targeted towards young children, has been popular for generations.

岡元さんの作品写真